Holy Days in the Christian Week

A final word this week on Liturgy and Time, from A.G. Martimort's classic four volume work, 'The Church at Prayer'. I have noted that liturgical time is blessed and sanctified by prayer and reveals Christ's redeeming work. As such, the week, centred on the day of the Lord, Sunday, is a sacramental of redemption and the new creation in Christ. Since the era of the early Church, certain days in the week have had a special significance, just as certain days in the year have a significance, revealing an aspect of the Paschal Mystery. Martimort explains:

A final word this week on Liturgy and Time, from A.G. Martimort's classic four volume work, 'The Church at Prayer'. I have noted that liturgical time is blessed and sanctified by prayer and reveals Christ's redeeming work. As such, the week, centred on the day of the Lord, Sunday, is a sacramental of redemption and the new creation in Christ. Since the era of the early Church, certain days in the week have had a special significance, just as certain days in the year have a significance, revealing an aspect of the Paschal Mystery. Martimort explains:"In the liturgical organization of the week three days were very soon given a privileged place: Wednesday, Friday and Saturday.

As early as the end of the first century, the Didache speaks of Wednesday and Friday as fast days. In the next century, the Shepherd of Hermas, Clement of Alexandria and Tertullian speak of them as 'stational' days, that is, days of fasting and penitential prayer.

All of Christian antiquity, without exception, observed the Wednesday and Friday fasts. Rome added Saturday. In the West we find the discipline being softened between the sixth and tenth centuries: first, the Wednesday observance was reduced to one of abstinence, then the Wednesday abstinence disappeared, as did the Friday fast. Only Ember Wednesdays, Fridays and Saturdays remained as witnesses to the ancient discipline down to the Second World War.

Prayer on Wednesdays and Fridays became progressively communal instead of private, but the assembly held on those two days varied in form according to period and place. At Alexandria, in the middle of the fifth century, there was still an aliturgical assembly, that is, an assembly without any Eucharist. 'The Scriptures are read, and teachers interpret them; everything is done except the offering.' The historian Socrates, who attests this usage, adds that the preceding century Origen had written a number of his commentaries for use at the Wednesday and Friday gatherings. It seems that in the time of St Leo the Great Rome, too, had the custom of aliturgical stations on Wednesdays and Fridays.

On the other hand, the Churches of Africa, like those of Jerusalem and Cappadocia, used to celebrate the Eucharist on Wednesdays and Fridays. When, beginning in the sixth century, the West too began to celebrate Mass on these days, we see the lectionaries providing special epistles and gospels for these two ferial Masses, and this usage was to continue in France until the twelfth century.

It is easy to see why Friday was given a special place, but why did the Church decide to honour Wednesday, too, in a special way? St Epiphanius (d.413) echoing the 'Teaching of the Apostles' of the third century, says: 'Wednesday and Friday are spent fasting until the ninth hour, because when Wednesday was beginning, the Lord was arrested, and on Friday he was crucified.'

The Christian Saturday replaced the Sabbath but kept its name (Latin: sabbatum). This connection explains the very different attitudes the Church adopted in regard to Saturday. Some, in their concern not to judaize, refused to mark it by any special religious practices. Others, such as the Churches of Rome and Alexandria, made it a fast day beginning in the third century; the fast was meant as a weekly recall of the great paschal or Lenten fast. In the East, on the other hand, Saturday was drawn into the orbit of Sunday and became a feast day. Thus the Saturdays of Lent were assimiliated to the Sundays: there was no fast, the Eucharist was celebrated (whereas all the other weekdays were aliturgical), and the 'natalitia' (birthdays) of the saints were commemorated.

Beginning in the tenth century the custom spread in the West of honouring the Blessed Virgin in a special way on Saturdays. The Mass 'de Sancta Maria in Sabbato' (of Our Lady on Saturday), which Alcuin had inserted into his votive sacramentary, had by the twelfth century been given a place in the Lateran Missal. The Roman Missal of Pius V put its seal of approval on this devotion."

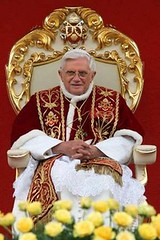

The image above shows a stational Mass in the church of Santa Sabina in Rome.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home