Beauty is of the Essence of Liturgy

Last week, the Church and the Order of Preachers rejoiced in the commemoration of Bl Fra Angelico, whose preaching was not exercised in word but by the brush, as he made visible for our contemplation the fruit of his contemplation of the true, the good and the beautiful. We often speak of God in terms of His goodness and His truth, but seldom do we engage in a theological aesthetic, finding God in Beauty, hence the particularity of Von Balthasar's theological project. I have touched upon aspects of Beauty and theology in this blog and I refer you to those posts for that is not my concern today. Rather, I would like to reflect on the need for Beauty in the Church which can, in turn, have such a profound effect on the world and our lives, as Beato Angelico's art did.

Last week, the Church and the Order of Preachers rejoiced in the commemoration of Bl Fra Angelico, whose preaching was not exercised in word but by the brush, as he made visible for our contemplation the fruit of his contemplation of the true, the good and the beautiful. We often speak of God in terms of His goodness and His truth, but seldom do we engage in a theological aesthetic, finding God in Beauty, hence the particularity of Von Balthasar's theological project. I have touched upon aspects of Beauty and theology in this blog and I refer you to those posts for that is not my concern today. Rather, I would like to reflect on the need for Beauty in the Church which can, in turn, have such a profound effect on the world and our lives, as Beato Angelico's art did.What can one say is special about Fra Angelico's art (above left, the Coronation of the Virgin) that gives it a religious, sacred quality? Pope Pius XII, speaking at the opening of an exhibition of paintings of Fra Angelico at the Vatican on 20 April 1955, explains:

"To encourage souls to pursue [holiness], Fra Angelico highlights not so much the effort of achieving virtue, as the bliss that comes from possessing virtue and the nobility of those adorned by virtue. The world of Fra Angelico's paintings is indeed the ideal world, radiant with the aura of peace, holiness, harmony and joy. Its reality lies in the future when ultimate justice will triumph over a new earth and new heavens. Yet this gentle and blessed world can even now come to life in the recesses of human souls, and it is to them he offers it, inviting them to enter in. It is this invitation which seems to us to be the message that Fra Angelico entrusts to his art, confident that it will thus be effectively spread.

It is true that an explicit religious or ethical dimension is not demanded of art as art. If, as the aesthetic expression of the human spirit, art reflects that spirit in total truthfulness or at least does not positively distort it, art is then in itself sacred and religious, that is, in so far as it is the interpreter of a work of God. But if its content and aim are such as Fra Angelico gave his painting, then art rises to the dignity almost of a minister of God, reflecting a greater number of prefections."

This is an extraordinary pronouncement because it accords to truly sacred art such a sublime potential and I would suggest that this refers not just to visual art but to music as well. Indeed, the Second Vatican Council pronounced that, "The musical tradition of the universal Church is a treasure of inestimable value, greater even than that of any other art" (Sacrosanctum Concilium, 112). Music has long been used in the service of the Liturgy, being instrinsically linked to the sacred texts of the Mass and Divine Office. When music and art in the Liturgy expresses the Beauty that comes from God alone, there is a raising of hearts and minds to God, to contemplate Him who is Beauty; an invitation to strive for holiness and that world where all is Beautiful. Thus, we ignore Beauty in the Liturgy at the risk of ignoring this vital means of drawing souls to Christ.

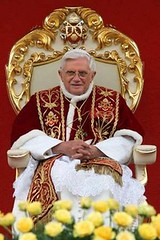

Martin Baker, Master of Music at Westminster Cathedral (photographed on the right) has an excellent article in the Tablet this week which reminds us that the Catholic choral tradition, such a key component of Beauty in the Liturgy, is "under threat and must be revitalised". In this article, he draws upon words written by fr Timothy Radcliffe, OP to support his argument and I think it is well worth adding his voice to the call for Beauty in our world:

"Jesus's sign at the Last Supper was beautiful. If it is to speak of hope in the face of death, then it must be re-enacted beautifully. Church teaching is often met with suspicion. Dogma is a bad word in our society. But beauty has its own authority. It speaks our barely articulated hope that there may be some final meaning to our lives. Beauty expresses the hope that the pilgrimage of existence does indeed go somewhere, even when we cannot say where and how. Beauty is not icing on the liturgical cake. It is of its essence"

Just to comment on the above, fr Timothy is absolutely right to say that Beauty is of the essence of Liturgy. This means that ugliness and banality in our Liturgy robs it of its essence and actually diminishes it. One may even ask: if Liturgy has lost its essence, if it is not beautiful, how much less efficiently does it fulfill its main purpose, which is the glorification of God and the sanctification of His People? Perhaps this is why many have lost interest in the Liturgy: because its contemporary celebration does not inspire, enthuse and fill with hope, because it is not beautiful and thus does not speak to the soul which thirsts for Beauty, for God. Is it not surprising then that people look elsewhere to slake this thirst? But of course, they find no actual satisfaction, for only Christ, the Fount of Life, the Living Bread, can fulfill our deepest desires and longings.

Moreover, fr Timothy suggests that Beauty in our Liturgy expresses our hope of a beautiful world to come, just as Pope Pius XII said that Fra Angelico's beautiful art was a reflection of the reality of the world to come, which was revealed to him in prayer and holiness of life. Hence, Michelangelo said of Beato Angelico: "One has to believe that this holy friar has been allowed to visit paradise and been allowed to choose his models there..." This suggests that the current drought of beauty in the Liturgy may be the result of what the Dominican Cardinal, Christoph Schonborn, calls "eschatological amnesia." Certainly, history informs us that when there was a great hope in the life to come, as in medieval Europe, the Church raised up great and beautiful Gothic edifices and performed a beautiful Liturgy that pointed to the Heavenly Jerusalem, the consummation of a Christian hope that was being expressed so eloquently in beautiful sacred art.

Returning to Fra' Timothy Radcliffe, he continues:

"C. S. Lewis wrote that beauty rouses up the desire for 'our own far off country', the home for which we long and have never seen... Beauty gives us a whiff of the Kingdom. George Steiner, in 'Real Presences', proposes that artistic creation is the nearest we can get to a sense of God's creativity... A beautiful work of art evokes that first 'Fiat' when God said, 'Let there be light'...

Often what we are offered at the Eucharist does not have the beauty that can speak of transcendent hope... If the Church is to offer hope to the young, then we need a vast revival of beauty in our churches. Most renewals of Christianity have gone with a new aesthetic, whether with plainsong in the Middle Ages, with Baroque music after the Council of Trent, or with Wesley's Methodist hymns in the late eighteenth century..."

Fr Radcliffe is surely right to call for a renewal of Beauty in our Church and in our Liturgy for beauty testifies to God and our Christian hope continually. Fra Angelico's art, the music of Palestrina and a beautiful church like Westminster Cathedral (on left) still speak to us today, as eloquent a 'sermon' as ever, preaching the Beauty of God who alone satisfies us and pointing to the world to come where the virtuous are united with God forever. Beautiful art have a freshness and immediacy that go beyond what is written on a page, endures where memory of a spoken homily fades and makes God accessible to all people, whatever their race, language or creed.

Therefore, Vatican II teaches: "These arts, by their very nature, are oriented toward the infinite beauty of God which they attempt in some way to portray by the work of human hands; they achieve their purpose of redounding to God's praise and glory in proportion as they are directed the more exclusively to the single aim of turning men's minds devoutly toward God" (SC 122).

And that - turning the hearts and minds of people to God - is precisely what the Church needs to do in a world already marred by the ugliness of sin, violence and hatred. The Church, through her Sacred Liturgy, must apply the balm of Beauty to our wounded world, so as to form in us the beauty of holiness.

May Our Blessed Lady, the Beautiful Mother of God and Blessed Fra' Angelico aid us with their prayers in this regard. Amen.

1 Comments:

A homily for the liturgical memorial of Blessed John of Fiesole, Blessed Fra Angelico

Memorial of Blessed Fra Angelico

Monastery of the Glorious Cross, O.S.B.

Branford, Connecticut

Blessed Fra Angelico is closer to us than you may think. In 2001, after years of sleuthing about and scientific analysis, curators and conservators confirmed beyond any doubt that an Italian renaissance altarpiece in the Yale University Art Gallery, a mere six miles away, is the work of Blessed Fra Angelico.

The altarpiece consists of four panels that would have originally closed over a tabernacle. The two upper panels depict the mystery of the Annunciation. On the left side is the Angel Gabriel in flight. His garments are intensely white, lifted up, and blown back in the intensity of his mission, or in the wind of the Holy Spirit. On the right side is the Virgin Mary seated and dressed in the blue of the Tuscan sky. On her lap is the open book of the Scriptures, suggesting that the Angel came to her during her lectio divina. She holds one hand over her heart expressing wonderment, but also telling us that the Scriptures held open in her lap are entering her heart as Word. She is the perfect illustration of what Saint James enjoins in today’s first reading: “Humbly welcome the word that has been planted within you” (Jas 1:21). The Virgin’s gaze, steady and humble, meets that of the arriving angel. Fra Angelico has painted more than a picture; he has opened a door and we are there, together with the Angel Gabriel and the Virgin Mary.

The lower two panels depict four saints: hearers of the Word. On the left side is Saint Francis of Assisi. With his left hand he parts the folds of his tunic to reveal the wound in his heart. Much later, artists will reproduce this very same gesture to depict the Sacred Heart of Jesus. For Fra Angelico, Francis is the icon of the Crucified, an icon within his icon. In his right hand, Francis holds out a Cross; he is announcing the mystery of the Cross, not in words alone, but in his wounded flesh. Fra Angelico takes great care to show the wounds in Saint Francis’ hands and feet. Being a maker of images, Blessed Fra Angelico is exquisitely sensitive to the images made by the hand of God. Saint Francis is just that, an image of the Crucified engraved by the hand of God in flesh, an epiphany of Crucified Love. Without speaking, Saint Francis is saying, “I bear on my body the marks of Jesus” (Gal 6:17).

Next to Saint Francis stands a holy bishop. The contrast between the bishop’s magnificent apparel and the humble sparrow-coloured tunic of the Little Poor Man is striking and, I think, intentional. The bishop’s mitre is white and gold, and inlaid with jewels; his ruby red cope is edged in a wide band of gold and parted to reveal a rochet of fine, almost transparent linen. One episcopal hand is raised in blessing; the other holds the shepherd’s staff, a crosier finely crafted of gold and set with precious stones. My eyes were drawn to the feet at the bottom of the panel. The bare, wounded feet of Saint Francis contrast with the toe of the bishop’s scarlet-slippered foot peeking out from beneath his robes. Taken together the two saints remind us that while there is but one path to the “holy mountain” (Ps 14:1) of today’s responsorial psalm, some are called to make the ascent with bare feet and others in scarlet slippers. It is not for us to judge but, rather, to rejoice in the diversity of gifts given by the one Spirit of holiness.

The right panel depicts Saint John the Baptist and Saint Dominic. They appear to be deep in conversation. The Baptist is dressed in the red of martyrs; a little bit of his robe of camel’s hair appears at his throat and hangs below his mantle. Is this to suggest that austerities are best hidden from view. Is it a Lenten teaching? “Your Father who sees in secret will reward you” (Mt 6:18). The Baptist, like Saint Francis, is barefoot. There is a holy connivance between them, that of the prophetic charism. Floating from the Baptist’s staff is a scroll announcing his mission: Ego vox clamantis in deserto, “I am a voice crying in the desert” (Mt 3:3).

Saint Dominic holds his head inclined in an attitude of reverent listening. Dominic the preacher is a listener to the Word, “quick to hear and slow to speak” (Jas 1:19). The Dominican tradition calls silence the Father of Preachers; holy silence engenders holy preaching. Dominic’s black and white habit frame the precious Book of the Gospels that he holds. Fra Angelico is telling us that the Gospel of Jesus Christ is central; the Gospel lies at the heart of Dominic’s preaching. The cover of the book is the same clear blue seen above it in the mantle of the Virgin, suggesting that both conceal and, in some way, reveal the mystery of the Word.

In his left hand, Saint Dominic holds a lily, the sign of a “religion that is pure and undefiled before God” (Jas 1:27), as Saint James says. Dominic has kept himself “unstained by the world” (Jas 27). Like the bishop in the panel facing him, Saint Dominic is wearing shoes, having “shod his feet with the equipment of the gospel of peace” (Eph 6:15). There is, nonethless, a difference: the bishop’s heavy robes fall over his feet, making swift movement difficult. Only his slippered toe appears. He is to preach, above all, from his seat in the midst of the local church. Dominic’s two feet, in contrast, are clearly visible. His tunic, like that of Saint Francis, is ankle-length, allowing for the freedom of apostolic mobility. “How beautiful upon the mountains are the feet of him who brings good tidings, who publishes peace” (Is 52:7).

Blessed Fra Angelico, the patron saint of artists, preached by making images, images of a radiant beauty, images conceived in silence under the overshadowing of the Holy Spirit, and brought to birth in prayer. Looking at his images and, today, giving thanks for the beauty of holiness in his life, we are, all of us, summoned with the saints to live with Christ on the “holy mountain” (Ps 15:1). The saints, some barefooted, some in slippers, and some in shoes, show us the way.

Post a Comment

<< Home