Beauty vs Aestheticism in the Liturgy

Once again, Disputations has asked some thought-provoking questions on the nature of Beauty. Of the three - Beauty, Truth and Goodness - which point to God, this is probably the most difficult to ascertain and define and hence the one least discussed or trusted. Co-incidentally, I have been pondering the issue too...

Once again, Disputations has asked some thought-provoking questions on the nature of Beauty. Of the three - Beauty, Truth and Goodness - which point to God, this is probably the most difficult to ascertain and define and hence the one least discussed or trusted. Co-incidentally, I have been pondering the issue too...Previously, I have written about the religious and theological value of beauty, especially in relation to the Sacred Liturgy. Since then, I have been invited to contribute to 'The New Liturgical Movement' blog, I have read about and commented upon a Mass that was celebrated in Singapore using the 1962 Missal - the first ones approved by the bishop since 1970 - and I have been reading and thinking more about the role of beauty in the Liturgy. It is the frequent appeal to beauty in the Old Rite (and the alleged lack of it in many celebrations of the Novus Ordo) which has led me seek more answers on the issue of Beauty.

In the course of all this, I have been pondering the fact that oftentimes, Liturgy and the role of Beauty and the arts at its service, has been reduced to a matter of taste and superficial aesthetics. Thus people even boycott certain Masses in favour of more 'beautiful' or 'artful' Masses. More particularly, I have been wondering how we get around the fact that oftentimes, "beauty is in the eye of the beholder". Hans Urs von Balthasar is renown for his theological aesthetics and metaphysical perspective on true Beauty and I have tried to highlight some of this in a previous post. However, I feel there must be more to be said on how we may distinguish between mere aestheticism and beauty.

For it seems we are all drawn to Beauty, in some way, but not all moved by it to contemplate and worship God. People listen to glorious sacred music or visit sumptuous cathedrals, but while delighting in the beauty of the art therein, they appear to see these as hallmarks of mankind's creativity and thus glorify man more than God. Why is this so? And is something truly more beautiful because it is inclined toward the divine? Something about Gregorian chant must endue it with such 'divinizing' values for the Church to consistently uphold plainsong above all sacred music and arts.

In my reading, I have come across an incisive and fiery book by Dietrich von Hildebrand called 'Trojan Horse in the City of God'. Much of it is a scathing critique of the post-Conciliar Church and the attitude which pervaded the Church in the aftermath of Vatican II. Most of what he says, in my opinion, is still very relevant and an accurate analysis of our current situation. I would highly recommend this book, because it is certainly thought provoking and raises some crucial questions. But what is of use to the questions above may be found in chapter 26 of the book, 'The Role of Beauty within Religion'. Having re-read it recently, I offer extracts here to help guide us in discerning what is Beauty and thus of value and what is mere aestheticism and self-indulgent, and a hinderance to true Liturgy and Religion.

"Beauty plays an important role in religious worship. The very act of worshipping a divinity implies a desire to surround the cult dedicated to this divinity with beauty. To stigmatize as aestheticism the concern for beauty in the religious cult (as some Catholics have been doing lately with increasing stridency) betrays a distorted conception of religious worship as well as the nature of beauty. This becomes clear when one considers the nature of aestheticism instead of merely employing the term as a destructive slogan.

Aestheticism is a perversion of the approach to beauty. The aesthete enjoys beautiful things as one enjoys good wine. He does not approach them with reverence and with an understanding of the intrinsic value calling for an adequate response, but as sources of subjective satisfaction merely. Even if he has a refined taste and is a remarkable connoisseur, the aesthete's approach cannot possibly do justice to the nature of beauty. Above all, he is indifferent to all other values that may inhere in the object. Whatever the theme of a situation may be, he looks at it solely from the point of his aesthetic enjoyment or pleasure. His fault does not lie in overrating the value of beauty, but in ignoring the other fundamental values - above all, the moral values.

To approach the situation from a point of view that does not not correspond to its objective theme is always a great perversion. For example, it is perverse for a man to approach a human drama that calls for compassion, sympathy and helpful action as if it were merely an object for psychological study. To make scientific analysis the only point of view in every approach is radicallly unobjective and even repulsive; it disregards and nullifies the objective theme. Apart from ignoring all other points of view than the 'aesthetic' and all other themes than that of beauty, the aesthete also distorts the real nature of beauty in its depth and grandeur. As we have shown in other books, all idolization of a good necessarily precludes understanding its true value. The greatest, the most authentic appreciation of a good is possible only if we see it in its objective place in the God-given hierarchy of being.

If someone were to refuse to go to Mass because the church was ugly or the music mediocre, he would be guilty of aestheticism, for he would have substituted the aesthetic point of view for the religious one. But it is the antithesis of aestheticism to appreciate the great function of beauty in religion, to understand both the legitimate view it should play in the cult and the desire of religious men to invest the greatest beauty in all things pertaining to the worship of God. This correct appreciation of beauty is rather an organic outgrowth of reverence, of love of Christ, of the very act of adoration...

The way in which this mystery [of the Holy Mass] is presented, its visible appearance, plays a definite role and cannot be considered subject to arbitrary change despite the fact that the thing expressed is incomparably more important than its expression. Although the real theme of the mass is the making present of the mystery of Christ's sacrifice on the Cross and the mystery of the Eucharist, a great weight should nevertheless be put on the sacred atmosphere generated by the words, the activities, the accompanying music, and the church in which it takes place. None of these things can be considered to have a merely aesthetic interest... Moreover, the sacred beauty connected with the Liturgy never claims to be thematic, as in a work of art; rather, as expression, it has a serving function. Far from obscuring or replacing the religious theme of the Liturgy, it helps it to shine forth... To stress that the Liturgy should be beautiful in no way amounts to the colouring of religion with an aesthetic approach. The longing for beauty in the Liturgy simply arises from the sense of the specific value that lies in the adequacy of expression.

The beauty and sacred atmosphere of the Liturgy are not only something precious and valuable as such (as adequate expressions of the religious acts of worship), but are also of great importance for the development of the souls of the faithful. Time and again those in the liturgical movement have stressed that mawkish prayers and hymns distort the religious ethos of the faithful; appealing to centers in men that are far removed from the religious one, the draw him into an atmosphere which obscures and blurs the face of Christ... The Gregorian chant is being replaced at best by mediocre music, at worse by jazz or 'rock and roll', Such grotesque substitutions veil the spirit of Christ immeasurably more than did former sentimental types of devotion. Those were certainly inadequate. However, jazz is not only inadequate, but antithetical to the sacred atmosphere of the Liturgy. It is more than a distortion: it also draws men into a specifically worldly atmosphere. It appeals to something in men that makes them deaf to the message of Christ...

The Catholic Liturgy excels in its appeal to a man's entire personality. The faithful are not drawn into the world of Christ only by their faith or by strict symbols. The are also drawn into a higher world by the beauty of the church, its sacred atmosphere, the splendor of the altar, the rhythm of the liturgical texts, by the sublimity of the Gregorian chant or by other truly sacred music... Even the odor of incense has a meaningful function to perform in this direction. The use of all channels capable of introducing us into the sanctuary is deeply realistic and deeply Catholic. It is truly existential and plays a great role in helping us lift up our hearts."

There is surely much more that can be said on the issue, but for now, I wish to add this voice to the discussion as we continue to seek true Beauty and approach God with a true re-discovery of Beauty within the Liturgy.

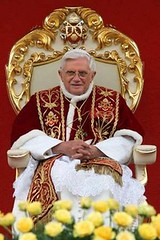

The photos above are courtesy of the Juventutem website and others.

2 Comments:

Your right 'Trojan Horse in the City of God' is really worth reading. I read it a couple years back and he is mostly right on.

Thank you for posting this. The temptation to be merely an aesthete is a difficult one for me, and I need occasional reminders like this one that aestheticism "is a perversion of the approach to beauty."

Post a Comment

<< Home