Life and Spirituality of St Thomas Aquinas - Prima Pars

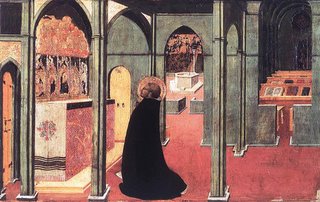

On the Feast of St Nicholas in 1273, St Thomas was celebrating Mass (a practice which, unusually for that time, he did daily) in the chapel of St Nicholas in Naples. His biographers say that in the course of celebrating this Mass he underwent an astonishing transformation (mutatione): “After that Mass, he never wrote further or even dictated anything, and he even got rid of his writing material”, leaving uncompleted the third part of his Summa Theologiae. When he was asked by Reginald of Piperno, his socius, why he was doing no more, St Thomas simply said: “I cannot do anymore. Everything I have written seems as straw in comparison to what I have seen.”

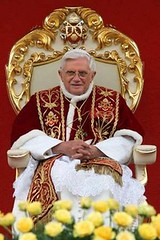

This incident which we will examine later is called by some ‘the silence of St Thomas’ and it marks a turning-point in the eventful life of the friar who has been exalted by popes as the ‘Angelic Doctor’ and the ‘Common Doctor of the Church’, a title that was already accorded him in the 14th century. As Guy Bedouelle, OP says: “His philosophy is taken for granted as perennial, and his theology merits the same tribute.” Moreover, he alone is singled out in our Constitutions (art. 82) as “the best teacher and model” for the study characteristic of a Dominican. More recently in Fides et Ratio (1998), Pope John Paul II said, “the Church has been justified in consistently proposing Saint Thomas as a master of thought and a model of the right way to do theology” and “In him, the Church's Magisterium has seen and recognized the passion for truth”(art. 44). As such, he is probably the best known Dominican, although for me – and I suspect many others – he was so much in a class of his own, that I was quite unaware that he was a Dominican – he was just the Thomas Aquinas! However, as we shall see, St Thomas’ approach was profoundly Dominican and steeped in his religious life. As Richard Woods OP says: “Thomas’ scholarly work was inseparable and indeed rooted in his personal spirituality, itself grounded in his Dominican identity” and it has been said by many that his “theology overflows into the spiritual life or, if one wishes, into mysticism.”

My aim is to merely introduce some of these ideas and St Thomas’ spiritual insights. If I’m only a catalyst in causing you to discover for yourselves our brother, Thomas’ writings, I will be entirely satisfied and grateful!

Sources

Bedouelle is right to say that “with the possible exception of St Augustine and Shakespeare, there is no other writer whose work has been commented on, compared to other thinkers and subjected to criticism more than that of St Thomas Aquinas.” Indeed, after a falling off after Vatican II, the last decade or so has happily seen a revival of interest in St Thomas and his theology. Quite apart from these, there is the massive corpus of writings by St Thomas himself.

But there are clearly some books which I have found more helpful than others. I have had recourse to some of his writings, particularly the famous Summa Theologiae. Chief among the books written about St Thomas is the excellent two-volume 'Saint Thomas Aquinas' by Jean-Pierre Torrell, OP. I believe this is currently the best monograph available, very readable and interesting and it supersedes the earlier work by James A. Weishepl, OP. I have used both extensively.

I have also referred to Simon Tugwell OP’s ‘Albert & Thomas’, Hinnebusch OP’s ‘The History of the Dominican Order’, ‘Mysticism & Prophecy’ by Richard Woods OP, ‘Aspects of Aquinas’ by Francis Selman, ‘Discovering Aquinas’ by Nichols OP and ‘In the image of St Dominic’ by Guy Bedouelle OP, among others!

Finally, classic writers on Aquinas whom I have found helpful are Marie-Dominique Chenu, OP and the Thomist scholar, Josef Pieper.

Biography with Spiritual characteristics

Tommaso d’Aquino was born in 1225, possibly on April 16. He was born in the family castle of Roccasecca, located in what was then the county of Aquino and almost midway between Rome and Naples. His father, Landolfo was descended from the counts of Aquino (and may have been a knight) and had at least four sons and five daughters with Theodora; Thomas was the youngest. It was customary for “upper-class families to present their younger boys as oblates to monasteries.” Thus Thomas studied with the Benedictines (accompanied by his nurse) from 1231 at the ancient abbey of Montecassino and indeed, his family had hopes that he would later be made abbot, a position of some power and influence. But in 1239, he left the monastery (due to hostilities between the pope and Emperor Frederik II around the area of Montecassino) and was transferred by his family to Naples, for safety. At the university in Naples, he was taught by Peter of Ireland who introduced Thomas to the philosophy of Aristotle, which was becoming current in Europe as the whole corpus of Aristotle was being translated into Latin from Arabic texts. He was also taught the works of Averroes and Tugwell says that "It was no doubt partly because of his early studies in Naples that Thomas had a much sharper awareness of than Albert [the Great] did of the differences between Aristotelianism and Platonism."

In Naples too, Thomas became acquainted with the Dominicans whose priory was opened in 1231. Interestingly, there were only two friars in the house in 1239 because the emperor had expelled all (other) mendicants from his realm! One Fra John of San Giuliano inspired Thomas to take the habit of the Order of Preachers in April 1244. Why did Thomas choose this new Order? Clues to his spirituality may be found in this choice. Torrell suggests a “desire to live a life of poverty”, an aversion to ecclesiastical preferment (he rejected the abbacy of Montecassino and later refused the archbishopric of Naples and a cardinal’s hat), an inclination towards study and “according to the theory he developed later, if it is good to contemplate divine things, it is even better to contemplate and transmit them to others” (IIa IIae 188, 6; cf IIIa, 40, 1 ad 2; 2). However, he always had a “deep esteem” for the Benedictine ideal and he had a habit of regularly reading Cassian’s Conferences throughout his life.

Nevertheless, Thomas’ rejection of Montecassino clearly annoyed his ambitious parents and his mother raced to Naples to stop him from joining the Order but the wily friars of Naples (who had to deal with a similar problem in 1235) had sent him to Rome. She raced there but again she’d missed him; he was on the way to Paris with the Master General, John the Teuton. She sent a courier to her sons who were fighting in the emperor’s army in the north of Rome. So, Thomas’ brothers intercepted him near Orvieto and placed him under “house arrest” in Roccasecca for over a year. Notably he was allowed visitors and Fra John came from Naples with a new habit for him! During this time he prayed, read the entire Bible and began to study the Sentences of Peter Lombard. He even convinced his sister Marotta to become a religious .

When it became clear that he could not be convinced otherwise, he was allowed to return to the Dominicans. It is important to state that this incident did not rupture Thomas’ bonds with his family. Torrell notes that Thomas frequently stayed at family castles in the course of his later travels and even came to his family’s financial aid – with papal permission!

So Thomas went to Rome and then in the summer of 1245, he journeyed to Paris with the Master General and spent three academic years there at the priory of Saint-Jacques. It is likely that the first of these was his novitiate year followed by two years of study with St Albert the Great and possibly in the Arts Faculty of the University where he did studied some Aristotle and pseudo-Dionysius. We have in fact transcripts of some of Albert’s lectures from this period written in Thomas’ own hand.

In June 1248, the General Chapter created a studium generale in Cologne and Albert was transferred there to teach, taking Thomas with him. Thomas spent four years in Cologne with St Albert the Great and it was likely that he was ordained in there. Torrell says that in this time, “Thomas was deeply impregnated with Albert’s thought”. Indeed, Thomas seems to have been an assistant to Albert, helping him compile some of his notes and may have done some teaching of his own. Weishepl suggests that during this period, Thomas wrote his earliest work, a Biblical commentary on Isaiah and gave cursory lectures on the Scriptures. It is worth looking at the key ideas in this text, Super Isaiam because there are ideas characteristic of his spirituality.

The young friar expounds that the Word of God is “a light for the intelligence. But affectivity also finds a place there [for] to meditate on the Word is joy. It also inflames the heart. Theological emotion – the charity that supernaturalizes our power of loving – is necessary in theology… In fact his whole anthropology appears in this sequence: intelligence, affectivity, heart.” Moreover, the "rumination on the Word does not find its end in itself. That Word is destined by God for His People." For Thomas, the attentive listening to the Word is a privileged way of acquiring the love of God, because the story of the favours God has done for us is eminently suited to awaken in us that love. Therefore, in a later commentary on the Creed, St Thomas enumerates five attitudes that we should have toward the Word of God: (1) We must listen willingly to it; (2) We must next believe in it; (3) We must also meditate on it constantly; (4) We must further communicate it to others by exhortation, preaching and enkindling and (5) We must complete it by being realizers of the Word and not forgetful hearers. And St Thomas concludes that these five attitudes were found in Our Lady. Thomas’ place as a Biblical exegete has been eclipsed by his theological works but it is noteworthy that in 1262/63 he was believed to have been requested by Pope Urban IV to write a running commentary on the 4 Gospels. This was so popular among preachers that in the 15th century it was called the ‘Catena aurea’, Golden Chain. As such Mulchahey says that “the Catena aurea still occupied a place apart because Thomas had decided to produce a synthetic reading of the Gospels based solely upon Patristic sources. In fact, some of the Greek material Thomas incorporated into the Catena thereby became available to a wide audience in the West for the first time. Thomas [also] used, most notably the acts of the first five ecumenical councils of the Church.”

In 1252, Albert recommended Thomas to the Master General to become a bachelor in Paris and to teach the Sentences. Paris then was a less peaceful place than Cologne, suffering from student riots in the 1230s and opposition to the mendicant orders and a general distrust of Aristotle. Despite having to contend with these forces and struggle to be incepted as a Magister in Sacra Pagina, Master of the Sacred Page, in 1256, Thomas persisted and at his inaugural lecture preached on the vocation of the theologian. In his words: “The minds of teachers… are watered by the things that are above in the wisdom of God, and by their ministry the light of divine wisdom flows down into the minds of students.” There is fundamental aspect of Aquinas’ thought in this: that all wisdom comes from God and is mediated through prayer. As such, he quotes James 1:5, “If people lack wisdom, they should beg for it from God and it will be given them.” Underlying all this is a profound humility, the one quality most spoken of with regard to Thomas’ sanctity. Indeed, Thomas’ use of the term sacra doctrina (divine teaching) is not mere piety. It points to the fact that “Only God is the Teacher in this sacra doctrina, just as only He is the [One who is] Taught.”

From 1252 to 1256, he wrote his Commentary on the Sentences and it is interesting to see in his choice of citations the influences on his teaching. There are more than 2000 citations from Aristotle, a third of these from the Nicomachean Ethics, followed by the Metaphysics, Physics and De Anima. St Augustine has under 1000 citations, then 500 for pseudo-Dionysius, 280 for Gregory the Great, 240 for John Damascene.

At this time (c.1256) he also wrote his Contra Impugnantes, a defense of the mendicants, which was clearly needed in Paris then. Tugwell summarises this work: “It is not merely legitimate, Thomas argues, it is highly appropriate that there should be religious devoted to study, teaching and preaching (with the hearing of confessions an important pastoral adjunct of preaching). Poverty, in the rigorous sense of mendicancy, is not merely permissible, it is the crowing glory of religious life. Manual labour, by contrast, is not an essential feature of religious life…” As such, Thomas sees study (and the Dominican life) as a vital contribution to the life of the Church because it saves souls, a spiritual act of mercy.

Unsurprisingly then in 1259 Thomas was present with Albert at the General Chapter at Valenciennes where they were appointed to a commission to suggest ways of promoting study in the Order. Thomas certainly saw study as important in the Order and especially to teach, as Dominican academics. As Tugwell notes: “[Thomas’] claim that teachers of theology, by teaching the preachers, do more than the preachers themselves do… is of a piece with Hubert [of Romans’] readiness to give far more dispensations to teachers than to preachers, on the grounds that teachers make the preachers, but preachers can always be replaced!” From 1256-1259 he wrote his first major set of disputationes, De veritate. Before he left Paris in 1259, Thomas began the Summa contra Gentiles, a defense of the reasonableness of the Christian faith and one that was part of his search for wisdom, another key to Thomas’ spirituality. Rather than being written for any specific group of infidels, it was written to have “a universal apostolic bearing”, useful for all times.

He addressed many questions of the day too in his Quodlibets and lectures in Paris and he often wrote in response to a need in the Church. Indeed, he composed 26 out of 90 works “on request”, whether from friends, or the pope, or the Master General. “Despite heavy teaching and writing responsibilities, Thomas never neglected these demands of intellectual charity, and in this lies one of the elements of his sanctity. For anyone seeking the means he adopted, the secret is not to be found in austerities or in special devotions, exterior to his intellectual life, but in the very concrete exercise of his intellect” (Torrell, 49-50).

During this time in Paris, he also preached, even though few of his sermons survive. Moreover, Mulchahey notes that even his Lenten sermons preached in 1273 was reworked and circulated by his brethren as a theological work and not a sermon. Nonetheless, we do have evidence of his sermons and “compared with a number of his contemporaries, Thomas distinguishes himself by his simplicity and sobriety, the absence of scholastic subtleties and technical terms… For an intellectual, Thomas’ preaching appears astonishingly concrete, supported by daily experience, concerned with social and economic justice… As to the content, his sermons repeat many themes favoured by the preachers of every time: the meaning of God, devotion to the Virgin, prayer, humility (Thomas loved the theme of the vetula [old woman] who knows more about God than a proud intellectual), but also… in the first place, concern for the essential, charity… Then, imitation of Christ… Finally, he strongly emphasizes the place of the Holy Spirit as a source of Christian liberty, the bond of ecclesial communion, the origin of our prayers, the realizer of petitions in the Pater” (Torrell, 73-74). Noteworthy is the sobriety of Thomas’ style and language. As Pieper explains: “He avoids unusual and ostentatious phraseology… the firm rejection and avoidance of everything that might conceal, obscure, or distort reality.” This indicates his commitment to communicating the Truth as simply as possible and also his humility. It is also something we could emulate in our communication of the Faith today!

To be continued: Thomas in Orvieto & Rome: the Corpus Christi Office

2 Comments:

Excellent - looking forward for the next installment.

Thank you... I hope Part 2 did not disappoint. It was hard to fit so much in... the actual talk took me over 2 hours including discussion!

Post a Comment

<< Home