Healing our Divisions

In his latest book, What is the Point of Being a Christian?, fr Timothy Radcliffe, OP (right, with others of the Dominican family) writes that "Christianity is gravely wounded in its ability to witness to the future unity of humanity, both because of divisions between Christians and divisions within the Churches." He then attempts to map out the characteristics that divide Catholics and proposes a way of reconciliation and fruitful co-operation. It is true that the lamentable disagreements within the Catholic Church has weakened her witness to unity in Christ.

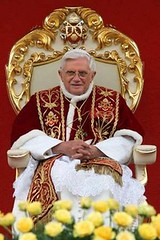

In his latest book, What is the Point of Being a Christian?, fr Timothy Radcliffe, OP (right, with others of the Dominican family) writes that "Christianity is gravely wounded in its ability to witness to the future unity of humanity, both because of divisions between Christians and divisions within the Churches." He then attempts to map out the characteristics that divide Catholics and proposes a way of reconciliation and fruitful co-operation. It is true that the lamentable disagreements within the Catholic Church has weakened her witness to unity in Christ.Such divisiveness is surely of the Evil One. Pope Benedict XVI said a few years ago, when he was still Cardinal Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith that far too much energy and resources were being expended by the Church with regard to her internal conflicts and structures. As such, little energy was left for the all important work of evangelization and the salvation of souls. There is much truth in this observation. I believe that we must beware of too much ecclesiastical navel-gazing and always remember that the Church exists in order to be a sacrament of salvation, a living sign of the Triune God Who is a Divine Community of diverse Persons in Unity. In the Trinity is our model of a community of love.

Therefore, this Octave of Prayer for Christian Unity does not only apply to inter-ecclesial communion but also intra-Ecclesial unity. As such, the following extract from Radcliffe examines what is necessary for Catholics - and also, by extension, all Christians - if we are to achieve greater communion and unity, to be reconciled in Christ so as to witness more effectively to the world; a riven and divided world in desperate need of the Gospel message of peace, unity, salvation and love. It is long, but please do keep reading! And so, Radcliffe writes:

"How are we to heal the wounds of Christ's body? How are we to learn to breathe again with the rhythm of the Eucharist, gathering people into community to share the Bread, and reaching out for the fullness of the Kingdom? In his sermon at the meeting of the Primates of the Anglican Communion, Rowan Williams reminded us that the Church is a sanctuary. He said:

'A sanctuary. But remember the two meanings of the word sanctuary in common use. A sanctuary, yes; a temple for God; but a sanctuary - a place of refuge, a place of asylum, to use a very current word. A place where those who need a home and have none may find it. So that

to be built by God into a sanctuary, a living temple, is not to be built into some closed space. It is to be built into a temple whose doors are open, where God is to be found and God's peace makes a difference. In all these respects, what deep conversion is required of us? How readily we turn to anxious striving, as if Christ had not died and been raised. How awkwardly we sit with one another to pray together and worship together. How easy it is for us to close our doors. But, we are called to be a kingdom of priests, and to be built as a holy temple so that the world may be invited, may see, may be transfigured.'

The Archbishop insists that the rebuilding of this home requires a deep conversion. I would like to explore in this chapter how this conversion must touch how we speak to each other within in the Church so as to heal division. Words can give life or death, hurt or heal.

In the beginning was God's Word, and that Word became flesh among us. At the heart of any Christian spirituality is our use of words. God entrusted Adam with naming the animals. This was a sharing in God's divine act of creation, speaking words that bring things to be...

Let us begin with the words that we do not speak, the silences that hurt the Church. Why do we say so little to each other? This silence has marked our words from the beginning. When God comes looking for Adam and Eve after their sin, they hide because they do not wish to talk. We have seen the silence of the women at the tomb. The silence within the Church was, it has been argued, intensified after the Thirty Years War in the seventeenth century.

It is impossible for us to imagine the sheer brutal horror of that war, in which Christians turned on each other with an unprecedented bloodthirstiness. One bitter fruit of that rending of the Body of Christ was a deeper silence. There were things that could no longer be discussed, either between Christian churches or within the churches. There was a new dogmatism. There was less discussion than in the medieval Church, in which one could argue for virtually any crazy proposition...

So the great wounding of Christendom in the seventeenth century introduced a weakening of debate within the Church. We had to toe the party line, to stick to precise formulations of dogmatic positions in the face of the enemy. Anyone who raised questions or entertained doubts was subverting the common cause... And there was just the same sort of dogmatism to be found in the Protestant churches as well.

It was not especially Catholic. It was just the beginning of modernity. We still have not left behind that silence. In 'Called to be Catholic', the founding declaration of 'The Catholic Common Ground Project', we are warned that 'across the whole spectrum of views within the church, proposals are subject to ideological litmus tests. Ideas, journals, and leaders are pressed to align themselves with pre-existing camps, and are viewed warily when they depart from those expectations.' The destruction of the common home of Christianity in Europe brought us centuries ago into a sort of politics of identity, which is why one must not project too cosy an image of the pre-Vatican Church, and this has intensified. One must say the right thing to belong. 'Is she sound?' Communion Catholics may ask. 'Is he open?' Kingdom Catholics ask in turn. 'Is he one of us?'...

The Second Vatican Council attempted to break this silence... But the Council left lots of things unsaid, or at least unresolved. Maybe that was necessary and unavoidable if the Council was ever to end. But we have since been haunted by what the Council did not say. The silence deepened in 1968, in response to 'Humanae Vitae'... It is important to see that this silence is not just a Catholic or a Christian problem... everywhere there are pressures to build communities of the like-minded. One form of this is the rise of political correctness...

Of course some things should not be said... Not everything can be said. But surely the Church must become a place of scandalous freedom in which we dare to float ideas, test hypotheses, affirm an awkward and unpopular truth, and tell the Emperor that he has no clothes on, or hear that we have none on ourselves. We can never draw near to the mystery unless we have the playful freedom of the children of God, to experiment and make mistakes, and grope after the truth. Time and again, we have seen that Christians should be the ones who go on asking questions when others stop.

How them are we to speak? What might be a spirituality of speaking and listening? It is the ascesis and delight of encountering those who think differently from ourselves, who feel differently, who inhabit different worlds. We each owe our existence to the encounter of difference. Each of us is the fruit of the meeting of a man and a woman... Difference is the source of fertility and new life.

One of the ways in which modernity tends to be sterile is that it fears difference and takes shelter in the same... Differences are far more painful to endure if they are found in people who are close, to whom one belongs. One tolerates odd views by strangers which would be intolereable in a sibling. One theologian, of the Communion tendency, confessed that he could only cope with the views of 'liberals' by pretending that they were not his fellow Catholics...

When we must deal with opponents then the typical model of modernity is that of the law court. When we cannot agree then the law must decide. Language is adversarial. Only one side wins. Often in the Church we too fall back on the adversarial, which is the rejection of a fruitful encounter. This happens on both sides... The later books of Hans Kung, a founding member of 'Concilium', often give the impression of being deaf to other positions, describing the views of 'the other side' in terms that render them absurd. This is a way of avoiding a serious engagement with other views. But many people on the other wing of the Church work in just the same way, scrutinizinng people's opinions for error, out to get people of unsound views, and to convict them of heresy. This is what John Allen calls 'Taliban Catholicism'. Cardinal Yves Congar wrote that the first condition of Church reform was caritas, 'that selfless, unsentimental love that wills only the good of the other'. This is not just a matter of the heart but of the head. It is using one's intelligence to understand those who are different. It is speaking and listening in ways that create communion.

Ludwig Wittgenstein wrote that 'the meaning of a word is its use in the language'. How is the other person using this word? It takes time and attention to discover this. I must see its role in his or her life. If it is used in ways that surprise me, then I must try to understand what is going on, what he is doing with the word... When we speak about what is most profound in our hearts, then we speak from somewhere.

We speak out of the 'gaudium et spes', the victories and defeats, that have shaped our lives and minds. We are each the inhabitant of a mental home, some bounded and shaped place, with its maps and signposts. This give us identity. But each such home offers its own access to God, its window on eternity... One might say the same thing about a good spirituality too. Particularity is the starting point on one's journey to the infinite and the universal...

This attention to the other demands that I accept that he or she may hold firm to truths which do not sit easily with what I believe. Their convictions are different. Remember the words of Bishop Christopher Butler to the [Second Vatican] Council, 'Ne timeamus quod veritas veritati noceat', 'Let us not fear that truth can endanger truth.' No encounter can be fertile unless I dare to entertain, at least for a while, convictions which appear to be incompatible... When I dare to entertain two truths that seem to be incompatible, then I am forced to look for the larger horizon in which they may be reconciled. This means that I must be drawn beyond loyalty to any party with its manifesto, by a more fundamental loyalty, which is to the truth. For it is the truth that will set me free. It is in the truth that liberates that Kingdom and Communion Catholics can meet...

This is not to say that one can believe what one wants, because God is so broad-minded that the truth does not matter. I cannot imagine God saying, 'Oh, so you think my son married Mary Magdalene, do you? That's fine by me. Da Vinci Code or the Summa Theologica? It's all the same to me.' The spaciousness of God is more exciting than mere indifference. The good shepherd leads his sheep out of the tight and tiny boxes in which we lock ourselves into his spacious pastures. We must trust the voice of the shepherd who liberates us from narrow ideologies and small vocabularies. We must find ways of speaking which reach for the spaciousness of God's word.

How different can two believers be for the encounter to be fertile? Of course ultimately we must share orthodoxy, but this is not to narrow the scope of the conversation; it is to enter the broad terrain of the mystery, in which we are liberated from the tightness of ideology. It is a serious misuse of language to use the word 'orthodox' to mean conservative, or even worse, rigid. Orthodoxy does not lie in the unvarying and thoughtless repetition of received formulas. As Karl Rahner pointed out, that can be a form of heresy. Orthodoxy is speaking about our faith in ways that keep open the pilgrimage towards the mystery. Often it is hard to know immediately whether a new statement of belief is a new way of stating our faith or our betrayal. It takes time for us to tell... It is a failure of courage to rush into condemnation... Even if someone says something which is clearly unorthodox, my first reaction must be to see what truth they are trying to say rather than immediately condemn their error. They may be struggling to say something true, even if they are putting it in a way that is untrue... Noel O'Donoghue once described heresy as 'trapped light'. One must find a way to let out the light that is there.

All this demands patience... At this stage one may be tempted to think this all sounds very lovely, but will anything happen? To heal the polarization of the Church we need more than a spirituality; we need action. I would briefly suggest that we need two things: places in which such conversations can take place, and leadership... We need lots more institutions, which open up spaces and places in which we may talk freely to those who are different and be fertile... Leadership is the task of every baptized Christian. That it might be in some exclusive sense the task of bishops seems to be a strange and very modern idea. Many of the great reformers of the Church like St Francis of Assisi and St Catherine of Siena and Dorothy Day were not bishops. They were not even ordained. They were lay people and often women. Benedict, whose name the present Pope has taken, was almost certainly not ordained.

The only understanding of Christian leadership that I find in accordance with the gospel is the obligation on each of us to dare to take the first step... We need a little creativity of Thomas, who wove together the seemingly opposed traditions of Augustine and Aristotle, to make a new and more spacious narrative."

May the Holy Spirit renew us, inspire us and give us courage to step out in faith, hope and love, seeking after his truth. Amen.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home