The Need for Christian Unity

"Let us try to see with an impartial eye what Christianity looks like to the outsider, to the ordinary man who has been brought up with practically no knowledge of its principles and way of life, who has only very occasionally been inside a place of worship, and has the haziest idea of what it is all about. Yet there are times when he feels vaguely uncomfortable. The world is becoming a more and more insecure place to live in, and the things he is compelled to do every day seem to him, when he can look at them in a detached frame of mind, increasingly meaningless. He appears to himself, when he thinks seriously about the purpose of life, as he does sometimes, to be a helpless unit caught up into and entangled in a vast system which makes little or no sense whichever way you look at it. Being almost overwhelmed at times by the thought of this apparent purposelessness, of toiling to make money for other people at a job which interests him little of not at all for its own sake, of marrying and bringing up children to live in the same way and for the same object; it is natural that he should sometimes turn to religion for consolation and perhaps explanation.

He turns to the Christian religion because it is easily accessible to him; it surrounds him, in fact, on every side, and he knows it at least in name. But he does not as a rule read books about it; still less does he consult one of its authorized teachers. He studies it in his own locality, sampling perhaps its places of worship, reading the cheap literature he finds displayed at the church or chapel door, and viewing with a critical and appraising eye the people whom he knows who profess it. As a rule, unless he is very fortunate, he comes away from his brief and perhaps not very intense effort to understand Christianity, with the conviction that it is considerably more complex, and makes if possible less sense, than the riddle of life itself. He may get the impression, from things he hears and reads in the course of his researches, that Christ was a very great teacher, who had a message for the world of his time, but he is quite sure that those who claim to represent him in the world of today have bungled his message and do not themselves know what he really taught. Its expounders talk a jargon of which he can make neither head nor tail, and the greater part of their energies seem to him to be occupied with the task of proving that every other form of Christianity but their own particular brand is wrong and therefore useless.

Today, moreover, there exists a small but growing body of men and women who have a clear-cut and logical view of life... They are professed materialists and their view of life is, in its essentials, the anti-thesis of the Christian view of life, and those of them who follow out their principles to a logical conclusion are strongly opposed to Christianity. Their opposition is made easier because Christians supply them with plenty of excellent ammunition by their seemingly endless divisions and disputes, and by their apparent preoccupation with these domestic squabbles to the exclusion of what the ordinary man regards as the really important things of life. Can we blame him for giving up the attempt to understand Christianity and beginning to listen to what its enemies have to say with such point and pungency, and can we be surprised if he comes to the conclusion that religion, at least in any organized form, is a hindrance rather than a help to the solution of the problems of human life? Even Catholics, careless perhaps of the duty of keeping their treasure intact in dangerous surroundings, or ill-instructed in the fundamentals of the spiritual life, can all too easily find that the discord around them and the agnosticism it results in are echoed in their own lives.

In face of this situation it is imperative that the divisions of Christendom should be brought to an end, that Christianity should speak to the world with a clear and united voice. What chance is there of this ever happening? Humanly speaking, it seems to be a very long way off indeed. But in this matter we have no right to speak only humanly. If Christendom is ever again united into a single body professing one faith, it will be because God himself wills it and brings it about. But though the work of reuniting Christendom is essentially a work that only God can do, we can hinder or promote the work of God by our human ideas and actions. The seed of reunion will only germinate and fructify by the power of the Holy Ghost. We can hinder its growth by leaving the ground unprepared; we can promote it by diligent spade-work. But if we are to take our part in doing this necessary spade-work, we must first be filled with a consuming desire for reunion. Our hearts must burn with charity and zeal for this end; we must be profoundly grieved by the thought that so many who profess the name of Christ are estranged and divided from each other...

We are, as Catholics, rightly conscious of our unique position in Christendom, and secure in our own divinely constituted unity and faith, but we are apt to forget that what is clear to us from within is by no means so obvious to the outsider. We pray dutifully for the conversion of our country and the world; we do not always recognize that the chief thing that hinders the conversion of our country and the world is the confusion in Christianity of which we appear to be but a part...

Catholics, when they speak of reunion mean not the joining together of the sundered parts of a divided Church, but the healing of those schisms by which millions of human souls have been cut off in the past and are still cut off from full participation in the visible unity of Christ's Mystical Body. But though it is axiomatic for us that the visible Church can never be divided and must always remain one, yet the Church may lose, and has lost, large portions of her visible membership, to the very great detriment not of its essential unity, nor of its essential life, which are divinely created and guaranteed, but of the fullness, completeness and richness of that unity and life...

For numberless ordinary people today Christianity is put out of court, not because they have examined its claims and found it wanting, but because in an age which has a vague longing for religion, yet is made supine by disintegrating elements of its civilization, Christianity as a whole does not speak its message in clear and decided tones so that all can hear and understand. And not until Christianity can speak again in the hearing of the world as it did in the Apostles' time, with a single, clear and certain voice, not until Christianity and the Catholic Church are again one and the same thing, will the conversion of the world really begin.

This, then, is the situation with which we are faced today. On the one hand a world growing more and more chaotic for lack of any stable guiding principle, a world crying out in sore need for the truth; and on the other hand, the Church, proclaiming the truth unwaveringly, in clear and insistent tones, but in tones that often remain unheard because its voice is drowned by those other voices, each claiming its own particular version of the way of salvation. There can be no doubt that the most urgent need of today, in face of the tremendous problem which the world must set itself to solve, is the reunion of Christendom, in order that the truth which Christ came to bring, and which alone can solve those problems, may be proclaimed in such a way that all may hear it because Christendom speaks with a united voice...

The stage is set for a life and death struggle, a greater struggle perhaps than has ever taken place in history since the struggle between paganism and Christianity in the first four centuries of the Church's life. This spiritual struggle has already begun; it is a struggle for supremacy between those who regard this life as an ultimate, and those who look to eternal life; the struggle between Christ and pagan humanism for the soul of the civilized world. If Christians, then, are to play their part in the struggle as it develops and grows in intensity, how urgent the need is that they be united, that they should bear a united testimony to the Truth as it is in Christ Jesus, that they should show to the world a concrete and visible realization that there is One Lord, One Faith, One Baptism...

Truth is always involved in a concrete situation; it has behind it a history and a tradition; it carries with it an atmosphere and it is held and viewed accordinly. In the contemporary world a Catholic's belief in the Church is held and lived and thought about in surroundings of opposition; among people who disbelieve in it, and are either indifferent to it or attack it and oppose to it a different doctrine. The consequence of this is that though Catholics hold the whole doctrine concerning the Church, as it is taught by the Church, they tend to emphasize disproportionately certain aspects of it; just those aspects that are denied by those amongst whom they live. For instance, we as Catholics hold the Church to be Christ's Mystical Body, and that our supernatural life in the Church through grace is life in Christ; Christ living in us, and we in him; that the Church is in consequence the fellowship of the redeemed in which all those who are baptized are incorporated. This doctrine is the fundamental basis of our belief in the Church; the primary thing we believe about it. From this doctrine flows that of the supremacy and infallibility of the Pope, which is the divinely constituted safeguard of life in Christ within the Church. But so heavily has the doctrine of the Pope's supremacy and infallibility been emphasized by the exigencies of controversy that it has come to be regarded by outsiders, and sometimes, I fear, by Catholics too, as almost the sole constituent of the Church's doctrine about herself.

The result is that the Church is often regarded merely as a juridical institution in which the keeping of certain laws has become substituted for a deep spiritual sense of life in Christ, an institution in which holding the Faith is unconsciously regarded as more important than living it. It is clear that here we have a defective presentation that gives rise to a false apprehension of the Faith on the part of non-Catholics; the more so that many of them themselves have a very strong evangelical and Pauline sense of the Christian life as being life in Christ...

The ecumenical spirit, then, may be described as a spirit of friendliness, sympathy and mutual understanding; a spirit which lays aside the psychology of war and rejects all controversy of the win-a-victory type, and which without surrendering one iota of principle attempts to enter into the minds of those who differ from us, trying to understand by careful and patient probing what the real extent of those difference is, and what caused them to arise. Those who are actuated by this spirit, and who adopt this method of approach to the differences which divide Christians, are as a rule profoundly convinced that the ultimate work of bringing about the unity of Christendom is not the work of men, but of God. The work of men is to prepare the ground, upon which the grace of God may work. This can be done by a firm determination to get outside our normal surroundings and to make contacts of sympathy and understanding with those whose

environment and tradition are very different from our own. The barriers of mutual suspicion and prejudice which divide us must be cleared away, and these can only be broken down by the more complete understanding that comes from personal contacts. To approach the differences which divide Christians in this spirit and by this method is to create a psychological atmosphere in which the Truth can emerge and be seen as truth."

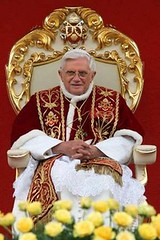

The icon above is 'The Mother of God Overshadowed by the Holy Spirit' by W.H. McNichols, SJ. She stands as the image of Mother Church, who will bring forth Christ the Eternal Word more eloquently, when She is overshadowed by the One Spirit who Unites us.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home