Faith and Certitude...

Station at Saint Mary Major's

Station at Saint Mary Major'sToday's Stational church is the Basilica of St Mary Major, also known Our Lady of the Snow. Built on the summit of the Esquiline hill in Rome in the 4th-century, the legend narrates how Pope Liberius was asked by a Roman patrician to build a church in honour of Our Lady and she indicated her preferred site to him by causing a miraculous fall of snow in August on the site. The church erected on this site was a titulus, or parish church under the patronage of the Pope and was built on the ruins of a pagan temple to Cybele.

The basilica was rebuilt by Pope Sixtus III in the 5th-century and it was dedicated to Our Lady following the Council of Ephesus in 431 which gave her the Christocentric title of Theotokos, God-bearer. It is the most ancient church in the West dedicated to the Blessed Mother, hence it's popular name and it is one of the four major basilicas of Rome. The relic of the manger in which Our Lord was laid is enshrined in this church and the ceiling of the church is said to covered with the first gold mined in the Americas.

This sumptuous church, with its beautiful mosaics depicting images of the divine Motherhood, is incidentally the Stational church for every Ember Wednesday in the Roman Liturgy. Four times a year, at the turn of the seasons, it was the custom in Rome to devote three days of that week (Wednesday, Friday and Saturday), to prayer and fasting so as to implore God's blessing on the new season and on the ordinations that typically took place during the vigil on the Saturday of the Ember week. As these traditions preceded even the liturgical seasons, they remained and often coincided with the seasons. As such, the Wednesday of the first week in Lent was an Ember Wednesday, hence the Station is held at St Mary Major, the appointed church for the four Ember Wednedays in the year. The revised liturgical calendar has dropped the Ember days but the Station celebrated at St Mary Major today is a reminder of the ancient tradition of the Roman church.

"This generation seeks a sign..." (Mt 12:39)

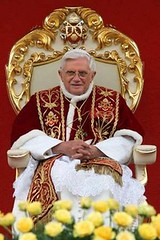

"This generation seeks a sign..." (Mt 12:39)The Holy Father's reflections from Journey to Easter (1983) on the readings of this first week of Lent continue today as he provides an analysis of the sign sought by our generation. He wrote:

"The Jews sought a sign - we too are 'the Jews'. Modern theology often stands looking for scientific certainty, in the sense of the natural, empirical sciences and, with this for a starting point, is obliged to reduce the Gospel message to the dimensions of such demonstrability. I think that an error such as this, on the level of demanding certitude, is what is at the heart of the modernist crisis reappearing since the Council. Behind such a phenomenon stands a reduction of the concept of reality, and behind this tendency is to be found a spiritual reduction, a myopia of the heart too full of the search for physical power, possessions, having..."

This crisis that Ratzinger highlights is evident in certain sectors of the Church. All too often there are misguided attempts to diminish mystery - be it in Liturgy, Scriptural exegesis, or theology - and to spuriously apply psychology, sociology, anthropology, etc.

By placing one's trust in scientific proof, seeing only what the natural sciences can empirically explain or what academic disciplines can rationalise away as 'real', faith and religion itself is rejected because it lacks that kind of scientific 'certitude'. Here in Britain, I have observed regularly a sustained onslaught against religion and faith by the press and the media. Lampooning religion and those with faith as irrational and unscientific, the secularist and atheistic propagandists appeal to a desire for certitude among those who live in a fraught and uncertain world. Playing upon such fears, there is an appeal to science as the 'one sure thing' that provides the answers to our questions in an all-too-tentative world.

But not all questions, especially the most profound questions about life, can be answered by science; that would be to demand answers beyond its scope, a most unscientific approach. Afterall, would one ask a physiologist why it is that the monsoon rains fall in India? Or ask a chemist what are the causes of urban migration in China? "It's not my field" they would rightly and justly say! So when questions about life, death, the soul, morality, etc are asked, an honest scientist should say, "It's not my field", for such questions are metaphysical (quite literally, beyond physics, the physical) questions and belong to the realm of philosophical and religious inquiry. So Ratzinger says:

"To be redeemed, to place ourselves within the truth of the creative mind of God, we must rise above the region of physical, tangible things, not only rising above them but attaining to the new certitude of a reality more profound, more real - spiritual reality. This journey, consisting in abandonment and overcoming, is the one we call faith. The claim of physical proof, of the sign which excludes all doubt, hides a refusal of faith, the refusal to rise above the commonplace security of the everyday and thus also the refusal of love, because love of itself demands an act of faith, an act of self-abandonment."

It noteworthy that the Pope says that in asking these metaphysical questions and seeking the answers from God, from religion, one has to rise above the need for scientific-type certitude. It is all too easy for people to transfer their need for doubt-free certitude into religion and thus instead of making an act of self-abandonment, an act of faith, they turn their religion into an ideology and a weapon that feeds on a fundamental insecurity in the person.

Thus, there is the attendant danger that in this 'new certitude' of spiritual reality, one might still seek certitude and security in doctrinal formulations, leaving no space for the immense mystery of God which those doctrines, at best, try to express using limited human language and concepts. The temptation is certainly very strong for religious people to abandon the mystery of God who is always beyond our knowing, in favour of statements about God that 'excludes all doubt'. In such cases, one would actually no longer be living by faith! Biblical fundamentalism is just one example of this kind of faith-abandonment, so that the Scriptures are used as proof texts to bolster a pre-existent ideology, rather than as sacred texts which point to the mystery of God and above all, of a person, Jesus Christ.

Hence, Ratzinger goes on to say that Jesus is the Sign who alone gives meaning to the desires of every generation. But not the "faithless generation" (cf 11:29), who has to learn to see the Sign; the Sign of Love. Thus, he wrote:

"To see Jesus, learn to see him... Let us contemplate him in his inexhaustible words, contemplate him in his mysteries, as St Ignatius provides in his book of the Exercises: the nativity mysteries, the mystery of the hidden life, the mystery of the public life, the Paschal Mystery, the sacraments, the history of the Church... The Rosary and the Stations of the Cross have been for centuries the great school for seeing Jesus."

All this points to prayer and contemplation as the key to entering the mystery of faith, encountering the truth and reality of Christ who is the answer to all life's greatest questions and gives meaning to our very existence; the Being who holds us in being. Ratzinger goes on to point out other pitfalls for those who are not essentially rooted in prayer and contemplation. He says:

"We too look for proofs, the sign of success, as much in general history as in our personal lives. In consequence we wonder whether Christianity has in reality transformed the world, has exhibited that sign of bread and security of which the devil spoke in the desert. The argument of Karl Marx that Christianity has had time enough to give demonstration of its principles, to give proof of its success, to give proof of having created the earthly paradise, and that after so long a time it is necessary to start again with other principles - this argument, I say, succeeds with many Christians, and many think it is at least necessary to begin again with a very different Christianity, a Christianity without the luxury of an interior life, of a spiritual life. But it is in precisely this way that we prevent the true transformation of the world, whose beginning is a new heart, a heart open to truth and love - a heart freed and free."

Ratzinger's observation still holds true today and his concerns, articulated 23 years ago, are reiterated in his first encyclical letter, Deus Caritas Est, which seeks to renew the Church's charity by placing it in relation to God and rooted in the divine Love for mankind; a renewal of the heart which alone transforms and renews the world, transfiguring the world in God's image.

Thus His Holiness wrote that we need "a 'formation of the heart': [we] need to be led to that encounter with God in Christ which awakens [our] love and opens [our] spirits to others. As a result, love of neighbour will no longer be for [us] a commandment imposed, so to speak, from without, but a consequence deriving from their faith, a faith which becomes active through love (cf. Gal 5:6)."

With these words, the Pope draws together our reflections on faith which, as an act of self-abandonment, is predicate on love and how that faith provides the answer to the world's uncertainties and questions by offering Christ, the Sign of Love to all generations. We can only see this Answer in Christ if we open our eyes of faith through prayer and contemplation.

This Lent, let us intensify our prayer that we may encounter the Lord and see Him in our neighbour and so love them and by being so, transfigure all of creation. We ask Mary, the Mother of God to accompany us on this journey, for she above all creatures has most perfectly trodden this path.

The statue above is of Jonah by Lorenzetto.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home