O Clavis David

"O clavis David, et sceptrum domus Israel: qui aperis, et nemo claudit; claudis, et nemo aperit: veni, et educ vinctum de domo carceris, sedentem in tenebris et umbra mortis."

"O clavis David, et sceptrum domus Israel: qui aperis, et nemo claudit; claudis, et nemo aperit: veni, et educ vinctum de domo carceris, sedentem in tenebris et umbra mortis."'O Key of David, and sceptre of the house of Israel, you open and no man can shut, you shut and no man can open: come and bring bound out of the dungeon him who is sitting in darkness and in the shadow of death.'

"Like Job complaining about God and to God we pray, 'Come to deliver us and set us free!' This passion for freedom is the hallmark of the Jewish-Christian tradition: freedom from Egypt and from the iron furnace, freedom from the tyranny of that most cruel Pharaoh, the Devil, freedom from sin, from death and from hell.

But this passion for freedom presupposes a sense of not being free at the moment. We would not pray so insistently to the Root of David to come to set us free unless we knew that we were held bound in some sort of prison. We are free in faith surely, but not yet sure that we have given ourselves so completely to God that we are free with the freedom which, in principle, he has given us. We still have a sense of frustration, of not being able to do what we want to do. But real freedom never consists in an unlimited exercise of free choice. Real freedom means, rather, being able to do exactly what we want to do, because we want all that God wants and only what God wants. It is because we are frustrated even in our good ambitions that we pray the Lord to come and lead us out of the prison-house where we are limited and circumscribed against our will. The Latin text of the antiphon seems to imply, interestingly enough, that God can lead us out from where we are sitting in darkness precisely by leading us out bound, bound now to him. Paradoxically, our liberation takes the form of slavery where we find ourselves enthralled, spell-bound, captivated by his presence.

This prison-house from which we seek to be delivered is not, of course, the body, flesh and blood that Jesus now shares with us forever. It is not the material world, which we seek not to be delivered from but to see transfigured... This world saps our integrity and eats up our whole personality, giving us not freedom to do what we really want to do but a whole set of false wants and artificial and quite unnecessary 'needs'... From this system of false wants and falsely conceived needs we pray the Key of David to come and deliver us.

But the prison-house which ultimately holds people bound is the house of death itself, that realm which takes hold of us while we are still alive and which we begin to experience in all the frustration that we experience now. Hell, the kingdom of death, is but the logic of our present situation insofar as that situation is unredeemed. Hell does not strictly await a man, but is created by his arrival. So it is not so much the due punishment of our present as our present unredeemed being taken to its logical conclusion and seen in its pure form, if the word 'pure' may be allowed here. To this hell, as we affirm in the Creed, Christ himself goes. We do not just pray to him to take us out of problematic situations and particular places where we find ourselves unfree. We ask him to set us free from the ultimate possibilities of our unfreedom, from death itself. Here we pray in fellowship with the patriarchs and prophets of Israel, with all those kings who desired to see what we have seen but never saw it, and to hear what we have heard but never heard it... We pray to the Key of David to come, therefore, and to lead out the one man who is the human race, who is all of us bound together in one bundle of life... 'Come and deliver us from hell,' we say, from the pointlessness and meaninglessness of it all, the logic that holds us trapped. If we can pray, then we can hope. If we can pray, then we are in the hell of the patriarchs that was full of hope, not Dante's hell which was full of despair.

'Come, O Key of David.' The conqueror is the Christ who was dead, but look, he is alive forevermore. He is the key that opens the door onto a new creation and a new age. He opens the future to us, releasing us from the gloom of our own logic through the power of the keys. It is within this sort of perspective that we can see the significance of that sacrament that we usually associate with the keys, confession, the sacrament of post-baptismal repentance. We are always more or less liable to get ourselves stuck in our past, We tend not to let the record play on but to get it caught, so that the same trivial bit of the tune goes on repeating itself again and again. It's all so dull. That dullness is one of the worst features of sin, the typical dreariness of the shadow of death. The keys are there to lead us out from that prison-house of our own past, out of our habitual ways of thinking and feeling, away from all that dreariness into new possibilities where our feet are set at large... In confession we pray to the Key of David to come and lead us out from all this, to bind us with his love and loose us from other loves.

'Come, Key of David', we sing on 20 December. In the Middle Ages they used to sing this antiphon at other times as well. In particular, they used to sing it when a recluse entered his cell or anchorhold, built alongside the parish church, perhaps, or by some monastery wall. As the recluse was walled up the bishop would lead the people in invoking the Key of David, praying that Christ might shut the door on the recluse in such a way that no man would be able to open it, but also to open doors before him so wide that man would be able to shut them. The recluse was cloistered in the strictest possible sense so that he might walk at liberty before God. He entered, in as symbolically literal a way as possible, into the experience of the Lord on Holy Saturday, going down alive into Hell, free amongst the dead, so as to help Christ harrow hell. His life was hidden with Christ in God, making visible in the walls of his anchorhold the hiddenness in God of every life that is lived with Christ. A life that is Holy Saturday is a very active life, a life engaged in the warfare against the demons.

Our wrestling is not against flesh and blood, it is not just problems on the sociological level, about timetables and inter-personal relationships. Our wrestling is 'against the spiritual hosts of wickedness', against demons whose very existence we have had never suspected until we entered some sort of enclosure of our bodies so that our minds might be free to serve him. Certainly, any kind of religious life worth the name must have some element of Holy Saturday about it. What have we to give to God except ourselves? And how do we give anything at all to God except by letting him give what he wants to us? And what does he wish to give us except that freedom for which Christ has set us free, the freedom which we taste in battling with him against the demons of our life-long cloister. The demand that makes on us, in terms of poverty and simplification of life, is that we should have no armour, no defence, save the shield of faith and the helmet of salvation, and the sword of the Spirit, which is the Word of God."

-Geoffrey Preston, OP, 'Hallowing the Time'

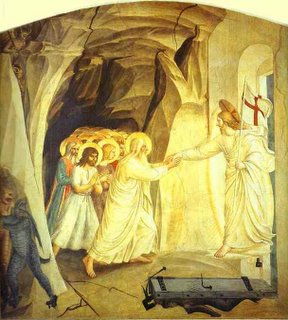

The fresco above of Christ harrowing Hell is by the Dominican beatus, Fra Angelico.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home