Fasting is for the Feasting

It is timely that today's Gospel mentions fasting, for we are about to enter a period of fasting in the Church, as we prepare for the nuptials of the Lamb. Indeed, the great Lenten fast begins this week on Ash Wednesday, which is itself a day of fasting and abstinence.

It is timely that today's Gospel mentions fasting, for we are about to enter a period of fasting in the Church, as we prepare for the nuptials of the Lamb. Indeed, the great Lenten fast begins this week on Ash Wednesday, which is itself a day of fasting and abstinence.So, these next two days, it may be helpful to prepare for that day by considering these two elements - fast and abstinence - and ask with Fr Geoffrey Preston, OP: 'What should be the place and significance of fasting for us?' In his book, 'Hallowing the Time', Fra' Geoffrey writes on this topic of fasting and it sheds light on today's Gospel too:

"The question is frequently sidestepped by thinking of the ways in which fasting may be useful for some purpose other than its primary one. Fasting might be valuable, for instance, as a means to the practice of almsgiving. We go without something, skipping a meal perhaps or giving up smoking for Lent, and we give what we have saved to a good cause. In recent years we have been encouraged to keep family fast days and to give they money we save to some international charity. Clearly, this is a good thing to do. And more than that, if we fasted in any one of these ways and then proceeded to pocket the cash we had saved for our own self-indulgence in other ways, it is hard to see what virtue there would be in fasting. Pope Leo the Great, whose sermons have marked so profoundly the Christian understanding of Lent, is quite firm on this point: 'Let our times of Christian fasting be fat and abound in the distribution of alms and in care of the poor; let everyone bestow on the weak and the destitute those dainties which he denies himself.' Fasting without alms-giving, then, can be simply self-indulgence or meanness towards oneself. Fasting with almsgiving, on the other hand, can make a difference, and a Christian difference at that, to the one world in which we live... Yet this is to treat fasting as just a means to the practice of almsgiving, rather than as an eminent good work in its own right, that eminent good work it has been conceived to be throughout the tradition by Jews and Christians alike...

To clear the ground for a proper appreciation of fasting we need to mention some of the provisos that Christian tradition has set around it. Fasting is of no Christian value unless it is integrated into a Christian lifestyle that includes relationship with God and other people... There is a second proviso which inevitably comes up when fasting is under review: the warning against Manicheism, against any disparagement of the goodness of God's creation. Some spiritual writers appear to be saying that fasting is a good thing because food and drink are bad things. They give the impression that if we are going to love God more, we must love what he has made less. St Thomas Aquinas is quite clear that if people have that spirit in their fasting then it is without Christian value. Fasting for him is part of the virtue of temperance, which deals with right relationship to the concerns of the body. Temperance means doing our righteousness, acting just right, in the areas of food, drink and sexuality in particular. For Thomas, there is only one vice in this, the vice of insensibility, of not having a proper esteem for the goodness, delight and attractiveness of the world God has made for our own good. Insensitivity, or not being sensitive enough, is a vice not so much of the head as of the fingertips. It means that we are required to experience the world as good and delightful. We are morally obliged to take a proper pleasure from our senses, to be happily alive in our skins. Thomas would include here the touch of food and drink on our taste-buds, the touch of a perfume on our nostrils, and the specifically sensuous and genital pleasures of sex. Now clearly, he is not telling us that in order to be virtuous we must be libertines; but he is teaching that if we are not duly sensitive to the delights that creation gives to our skins, we are less virtuous than we ought to be. If I don't appreciate a malt whiskey there is something wrong with me. If I am not moved by a woman's body I am lacking in goodness. And so fasting out of disdain for food, for all that business of cooking and eating and digesting and evacuating, is not an eminent good work. On the contrary, it is heresy in action. The desert fathers, those great heresy-hunters, used to set little tests for their visitors along these lines.

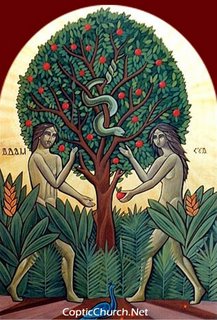

Jesus, nevertheless, assumes that his disciples will fast. He assumes it on the basis of Jewish tradition, just as that tradition assumed it from a wider religious tradition. Fasting is a general religious custom. According to Thomas, indeed, it is part of the natural law: if we do not fast we somehow fail in our common humanity. On the opposite side of the golden mean from insensibility lies the temptation to grab and snatch at the world, to turn it into a source of our own satisfaction. The story of the Serpent tempting Adam and Eve in the Book of Genesis is our best image of this temptation. The world is there for man to use: all the trees of the garden are for Adam to enjoy. Yet there are limits built into the world's order: not everything is to be enjoyed by our consuming it. There is a right way to enjoy the tree in the midst of the garden; but that right way is not to eat its fruit. Thomas talks of a lion looking at a gazelle and seeing only meat, none of the beauty of its line and form, none of the grace of its movement. Adam oversteps the mark by trying to grab everything for himself...

Fasting is about training ourselves to distiguish our needs from our wants. When we fast or abstain we give ourselves a chance to discover what our real needs are... Mark explains why Christians fast in an image of marital presence and absence. The days will come when the Bridegroom will be taken away from them, and then they will fast, on that day. Fasting as a response to the presence and the absence of Christ the Bridegroom belongs in the new covenant of grace. It undergoes a change of meaning, however, in the waters of baptism. For Christians, the material and bodily world is the world in which Christ has loved us so much that he sent his Son to it. This story of how God turned to us, finally and definitively, in love and mercy, is good news, good tidings of great joy. It means that the world is for feasting... And yet there is another, more sombre side to this picture. The world rejected the God who graciously accepted the world... So we cannot simply affirm the world as it is now... Our relation to the world is always nuanced...

Fasting from the food and drink of this present world is, for Christians, a sign of our expectation of the feasting in the new world, the world of the resurrection, on the food and drink of everlasting life. And just as you cannot pray without actually giving time to prayer, for it is nonsense to say that your life is a prayer if you never pray in the formal sense, so too you cannot learn to fast properly without some actual fasting from food. But the fasting is, ultimately, for the feasting."

1 Comments:

This is great ... thanks!

Post a Comment

<< Home