Joy and Hope for every Year

2005 has been called by some a year of natural disasters and indeed, it has seemed that way... such events as the great Asian Tsunami disaster and the earthquake in Pakistan have raised many questions in the hearts of people. There have also been tragedies brought on my human strife and evil... such as the on-going violence in Iraq and other places and the 7/7 bombs in London. And we have all on a personal level known sadness, grief and pain in this year, not least in the death of Pope John Paul the Great.

2005 has been called by some a year of natural disasters and indeed, it has seemed that way... such events as the great Asian Tsunami disaster and the earthquake in Pakistan have raised many questions in the hearts of people. There have also been tragedies brought on my human strife and evil... such as the on-going violence in Iraq and other places and the 7/7 bombs in London. And we have all on a personal level known sadness, grief and pain in this year, not least in the death of Pope John Paul the Great.But the Cross of suffering which all creation bears is not overshadowed by all that is good, true and beautiful, as the life of the late Holy Father witnessed to so eloquently! For in 2005, we have witnessed an out-pouring of love, generosity and good-will in response to every disaster and the launch of the Make Poverty History campaign. Indeed, I know that the amount of good news to recount in 2005 is simply too numerous to even begin! The little miracles of love, kindness, self-denial which we experience daily are too often over-looked in favour of more sensational headlines. Truly the Holy Spirit is active in these ways; healing, restoring and renewing and He gives us much to be thankful for.

40 years ago, the Second Vatican Council ended but it gave the Church and the world a vision to live by for generations to come. In its final document, Gaudium et spes, the Church spoke then as it does today of the human condition, of life, and declared: "The joys and the hopes, the griefs and the anxieties of the men of this age, especially those who are poor or in any way afflicted, these are the joys and hopes, the griefs and anxieties of the followers of Christ." Clearly then, joy and sorrow are part of humanity and of every year. But in every situation, the Church is and has been present, suffering alongside, offering hope and counsel, bringing the presence of Christ.

It is natural that disasters and being faced with the mystery of sin and evil should raise questions in us. This witnesses to the fact that we are naturally inclined towards good, life and truth. When these appear to be imperiled, we are rightly disturbed. Thus, the Council Fathers went on to say: "Nevertheless, in the face of the modern development of the world, the number constantly swells of the people who raise the most basic questions of recognize them with a new sharpness: what is man? What is this sense of sorrow, of evil, of death, which continues to exist despite so much progress? What purpose have these victories purchased at so high a cost? What can man offer to society, what can he expect from it? What follows this earthly life?

The Church firmly believes that Christ, who died and was raised up for all, can through His Spirit offer man the light and the strength to measure up to his supreme destiny. Nor has any other name under the heaven been given to man by which it is fitting for him to be saved. She likewise holds that in her most benign Lord and Master can be found the key, the focal point and the goal of man, as well as of all human history. The Church also maintains that beneath all changes there are many realities which do not change and which have their ultimate foundation in Christ, Who is the same yesterday and today, yes and forever. Hence under the light of Christ, the image of the unseen God, the firstborn of every creature, the council wishes to speak to all men in order to shed light on the mystery of man and to cooperate in finding the solution to the outstanding problems of our time."

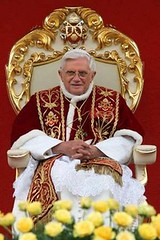

Thus, just as Pope Benedict XVI repeated to the youth gathered around him in Cologne, Christ is the answer to our longings, our fears, our hopes, our desire, our needs. On 18 August 2005, he said: "To all of you I appeal: Open wide your hearts to God! Let yourselves be surprised by Christ! Let him have “the right of free speech” during these days! Open the doors of your freedom to his merciful love! Share your joys and pains with Christ, and let him enlighten your minds with his light and touch your hearts with his grace. In these days blessed with sharing and joy, may you have a liberating experience of the Church as the place where God’s merciful love reaches out to all people. In the Church and through the Church you will meet Christ, who is waiting for you." It is worth asking if our Christian communities have been truly open to others, loving places where others may meet Christ.

We will all know people who are seeking answers to a myriad of questions, people who are confused or frustrated, angry with life or just drifting along indifferently. So the Pope said: "Dear friends, when questions like these appear on the horizon of life, we must be able to make the necessary choices. It is like finding ourselves at a crossroads: which direction do we take? The one prompted by the passions or the one indicated by the star which shines in your conscience?" But people can only make the choices for that which is good, true and beautiful if they listen to their conscience, finding Jesus in the goodness that lies in every human heart. People's goodness is aroused when they see goodness in those around them. As such, our Christian witness of love can reach out to Christ in others and reveal His light. As I have said before, I believe the key to this is Christian joy, happiness.

Returning again to the Holy Father's message: "Dear young people, the happiness you are seeking, the happiness you have a right to enjoy has a name and a face: it is Jesus of Nazareth, hidden in the Eucharist. Only he gives the fullness of life to humanity!... Be completely convinced of this: Christ takes from you nothing that is beautiful and great, but brings everything to perfection for the glory of God, the happiness of men and women, and the salvation of the world."

And so, with thanksgiving in my heart for 2005, and joyful hope in God's promises, it is not altogether cliched for me to wish all and sundry a HAPPY NEW YEAR!

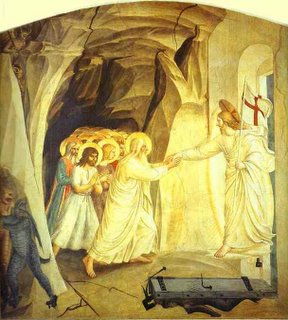

The image above is of Christ who suffers with us, by Sr Mary Grace Thul, OP.