Life and Spirituality of St Thomas Aquinas - Secunda Pars

However, he had been made a Preacher General at the 1259 Chapter, so he left Paris and returned to the Roman Province in Italy, where he spent a decade. During this period he spent quite a lot of time travelling, as he was a member of the Provincial Chapter. Tocco, Thomas’ oldest biographer says that he preferred contemplation and enjoyed travelling very little and only obeyed because, by the humility it inspires, obedience is the mother of all virtues. However, Torrell says “We can easily imagine the reasons for his repugnance: in addition to his corpulence, which could scarcely have facilitated things, the time passed in these comings and goings must have seemed lost from his other activities in writing and teaching…” including of course the desire to finish the Summa contra Gentiles. However, these journeys are not without significance for Thomas’ weltanshaung, for he describes humanity as viatores, travellers, on their way to their heavenly homeland. In his lifetime, Thomas travelled at least 9000 miles (15,000km) on foot!

However, he had been made a Preacher General at the 1259 Chapter, so he left Paris and returned to the Roman Province in Italy, where he spent a decade. During this period he spent quite a lot of time travelling, as he was a member of the Provincial Chapter. Tocco, Thomas’ oldest biographer says that he preferred contemplation and enjoyed travelling very little and only obeyed because, by the humility it inspires, obedience is the mother of all virtues. However, Torrell says “We can easily imagine the reasons for his repugnance: in addition to his corpulence, which could scarcely have facilitated things, the time passed in these comings and goings must have seemed lost from his other activities in writing and teaching…” including of course the desire to finish the Summa contra Gentiles. However, these journeys are not without significance for Thomas’ weltanshaung, for he describes humanity as viatores, travellers, on their way to their heavenly homeland. In his lifetime, Thomas travelled at least 9000 miles (15,000km) on foot!St Thomas was assigned to Orvieto certainly by 1261 and became conventual lector there. In this period he had time to turn his attention to “the widest variety of his writings”, including his masterly commentary on the book of Job. Nichols says these writings (opuscula) were “most commonly produced in response to requests from correspondents near and far, whether eminent or virtual nobodies”! The pope Urban IV took up residence in Orvieto in October 1262 and made full use of Thomas’ talents. I have already mentioned the Catena aurea but chief among Thomas’ work for the Church is his Office and Mass for the newly-instituted feast of Corpus Christi, including several hymns and a sequence.

Although many of us think of St Thomas and the Summa Theologiae as his great masterpiece, his work for Corpus Christi is arguably his greatest legacy. As Tugwell notes: “it is fitting that a theologian whose piety was so dominated by the Eucharist should have been the author for the liturgy for such a feast.” Indeed, “it seems that Thomas implied that the presence of Christ in the Eucharist was somehow the focal point and motivation of all his theology.” Clearly then, this is a highpoint! Singled out for comment is the sequence Lauda Sion which is “remarkable not only for its poetry, but also for its theological content; the individual stanzas can easily be aligned with the Eucharistic teaching of Thomas found in the third part of his Summa theologiae” (Weisheipl, 181). The significance of Thomas’ poetry and hymns is that we see an affective and creative side to him.

Tugwell and others point to Thomas’ great love for the Eucharist as a way to explain his silence after 6 December 1273. Although some people think he had a stroke or even a nervous breakdown, Tugwell suggests: “It looks as if Thomas had at last simply been overwhelmed by the Mass, to which he had so long been devoted and in which he had been so easily and deeply absorbed.” This suggests a mystical experience and so Hinnebusch writes: “Before every major occupation, whether debating, teaching, writing, or dictating, [Thomas] had recourse to prayer. His ardent love for God revealed itself in his fervent prayer before the Crucifix, in his intense love for the Sacrament of the Altar. His mystical intuition of divine things and his burning desire for union with God carried him at times into ecstasy. His mystical experiences reached such intensity towards the end of his life that all he had written seemed to him ‘so much straw’.” Such a realization, Tugwell suggests may be due to some ‘revelation’ he had, perhaps a glimpse of the Beatific Vision (suggests Richard Conrad, OP) that eclipsed all else and his love for Christ “became momentarily so intense that it crippled him, leaving him a stranger in the world.” Or one can take up Weisheipl’s view, as Torrell does, that Thomas experienced “an extreme physical and nervous fatigue, coupled with mystical experiences that marked his last year.”

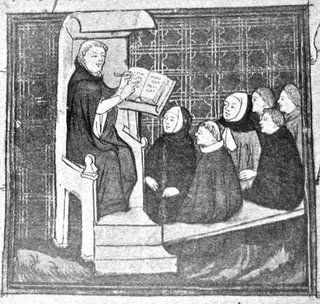

But returning to Thomas’s time in Orvieto: he spent five years there and then in September 1265, he was asked to move to Rome and set up a studium in Santa Sabina itself. He was given full authority over an unknown number of students sent to him from all over the Province of Rome to study under him. Leonard Boyle OP calls this “unique experiment” a studium personale, “a school organized as a forum in which a particular individual could share his expertise” (Mulchahey, 279). The fact that it did not survive Thomas’ departure from Rome is thus not surprising! Initially Thomas tried to re-use his commentary on the Sentences but this did not seem sufficient to him so he abandoned that by the end of 1266. Interestingly, a manuscript discovered in Lincoln College in Oxford in the 1970s is believed to be notes (taken by a student) from the first year of Thomas’ lectures in Rome as they are a “more incisively argued” version of his commentary written in Paris.

In his second and third years in Rome, Thomas began the great enterprise of writing the Summa theologiae and Mulchahey has worked out a sort of syllabus for Thomas’ Roman students that can be drawn from the prima pars. Certainly, by the time he left Santa Sabina to take up his second Regency in Paris in the summer of 1268, Thomas is thought to have finished the prima pars, which was already in circulation in Italy before he left for France. The bulk of the Prima secundae and the Secunda secundae were completed in Paris and the tertia pars in Naples, until 1273 when he stopped writing; thus he spent 7 years working on this text, a mark of its importance to him.

Amazingly, while at Rome, Thomas also had time to finish his Catena aurea, write disputatae and a Compendium theologiae, a simple and brief, unified exposition of Christian doctrine, written for his secretary Reginald, at his own request. As a mark of his spirituality, Thomas notes that he writes this small book in homage to the Lord who made Himself small in his kenosis. Moreover, St Thomas says here that salvation consists in three things: “To know the truth, which is entirely contained in the articles of the Creed; to pursue a just end, which the Lord taught us in the petitions of the Pater and finally, to observe justice which is summed up in the single commandment of charity.”

In 1268, Thomas was called back to Paris to combat the rising tide of students in the faculty of Arts who were following the Muslim philosopher Averroes’ interpretations of Aristotle with a disregard for their incompatibility with the Christian faith. Averroes (1126-1198) held that when Aristotle calls the intellect separate he means that there is a universal mind existing outside of us and which we all share. This view can still be found today: for example in the scientist, Erwin Schrödinger (d.1961), who clearly believed that we all have one consciousness. This clearly undermines the belief of Christians in the immortality of the individual soul and in free will because, if one’s mind is not really one’s own but an external one thinking in oneself, then one is not responsible for one’s own actions and so all meaning of reward or punishment in the next life for what one does in this life is removed (cf Selman, 17). Moreover, Paris was descending into more acrimony between secular clergy and mendicants in the university.

St Thomas addressed these contentious issues but he also carried on his daily work of teaching Scriptures and theology. Noteworthy is the manner in which Thomas deals with his opponents; indicative of his humility and search for Truth. Radcliffe notes Thomas’ respect for his opponents and suggests that like him, we too should strive to understand our opponents’ position and what they are trying to say before we begin any refutation or reply. By avoiding a caricature of our opponents’ position we show true respect for what they are saying and a careful attention to the Truth that is to be found. Radcliffe suggests that this is the model of the Summa.

Hence, between 1269-1272, St Thomas worked on the Summa theologiae and also wrote his commentaries on the Gospels of Matthew and John, the disputed questions on Evil and his massive commentaries on the Metaphysics and Nicomachean Ethics of Aristotle, using a new translation from the Greek by a Flemish Dominican. Thomas’ commentaries on Aristotle, which he engaged upon in Paris are interesting from a spiritual point of view because he “feels himself authorized to substitute for Aristotle in order to ‘extend’ him and make him say some things that he would not have been able to think.” Thomas “wanted to lead to its fruition the intuition that he thought had been Aristotle’s” and so bring him to the Truth in Christ that the pagan philosophers so longed for but sadly never saw. Torrell sees in this yet another mark of Aquinas’ “intellectual charity”.

Apart from these major works during his second Parisian stint, there are a host of smaller works on all sorts of issues; it is surely right for Tugwell to say that “Today, Thomas would probably be considered a workaholic”! What were his days like? He celebrated Mass daily early in the morning and then attended a second Mass said by another priest. He then immediately started lecturing and then began writing and dictating to several secretaries. After that, he ate, returned to his room and “attended to divine things” before having a short rest and then he wrote again. It is known that he generally only went to Compline in the priory although he attended more Offices when he was travelling and hence not teaching. What is amazing is that he sustained this pace of work for 25 years!

In 1272, he was summoned by his Province to Naples to organize a studium generale there. It was over a decade since he’d returned to his home convent and familiar faces greeted him, including Fra John of S. Giuliano who had inspired him to join the Order. In a beautiful way, his life had come full circle. It is believed that he taught a course on the letters of St Paul, in particular Romans. Of course, he also wrote his Summa theologiae reaching the summit of the work, on the Mass and then having moved on to the sacrament of penance, he stopped.

After the St Nicholas’ day event, Thomas becomes a “sick and rather helpless man”. He went to visit his sister but he appeared to be in a dazed condition and hardly spoke a word so he returned to Naples. In January 1274, St Thomas was summoned to Lyons for the General Council but on the way there, he was so absorbed in his thoughts – something quite normal for this friar – that he struck his head on a tree branch. This must have eventually developed into a blood clot in the brain that killed him. However, he carried on his journey, even wrote a commentary on St Gregory for the monks at Montecassino upon the abbot’s request; they had been waiting for him. Thus, even though his body was weakening, his intellectual faculties were still intact.

In late February, he stopped in the castle of Maenza, where his niece Francesca lived. It was there he fell ill and lost his appetite although at one point he asked for some fresh herring, a dish he enjoyed in Paris. Several days later, they tried to continue onwards to Rome but had to stop at the abbey of Fossanova. Thomas made this final journey on horseback, a sure sign of his weakness as Dominicans were forbidden to travel on horseback. On March 4 or 5, he received the viaticum and said: “I receive you, price of my soul’s redemption, I receive you, viaticum of my pilgrimage, for love of whom I have studied, watched, laboured; I have preached you, I have taught you; never have I said anything against you, and if I have done so, it is through ignorance and I do not grow stubborn in my error; if I have taught ill on this sacrament or the others, I submit it to the judgment of the Holy Roman Church, in obedience to which I leave now this life.” This final statement of faith is an indication of his deeply ecclesial spirituality, his humility and his love for Christ in the Eucharist.

He died on Wednesday 7 March 1274. I have not the time to dwell on the growth of his cult, the battle over his orthodoxy and the development of Thomism. Perhaps all this is already well known to us. It remains to say that he was canonized in 1323 and was proclaimed a Doctor of the Church by Pope Pius V in 1567.

The Person & His Appearance

I am intrigued by Thomas Aquinas the man… what did he look like? The witnesses are in agreement: “he was large and heavy and had a bald forehead.” Tocco says “he was large in body, tall and straight in stature… blond as the colour of wheat” and “his hair was thin.” Robust and strong would be other ways to describe him. About his character, Tugwell notes that “he was habitually silent”, perhaps lost in thought. Unlike Albert who observed the world around him and wondered about nature as he travelled, St Thomas was known to put up his hood and travel, lost in his thoughts. There is a story of him having dinner with king Louis of France when suddenly he exclaimed out loud that he’d solved some heretical proposition. Tugwell also suggests that “He seems to have had no small talk and perhaps he was rather devoid of humour.” However Torrell disagrees and notes contemporary accounts of Thomas’ “happy countenance, sweet and affable… he inspired joy in all those who looked upon him” as well as his ability to joke. Given the above we can understand better why he was nicknamed the ‘Dumb Ox’ – for his taciturn silence and his robust physique.

As for his affective life, it is a temptation to see him as a disinterested or reserved intellectual but that would be a mistake. We have the example of him joining in joyful communal celebrations to commemorate Reginald’s recovery from illness. His relations with his family and especially his sisters come across as affectionate, even emotional in a typically south Italian manner. Like Dominic and Jordan he was also known to be lost in tears as he said Mass and even during Compline, clear signs of his emotional expressiveness. As to his friends, we know he had a close friendship with Reginald and others. Indeed, Aquinas made friendship the key notion in his treatise on charity and indeed our relationship with God. Thus he says: “Charity is friendship between man and God, or the love with which man clings to God as to his friend.” This concept of divine friendship is quite unique I believe and it is difficult to think that the man who spoke in this way had nothing but a literary knowledge of affection and friendship.

Contemplation and Love

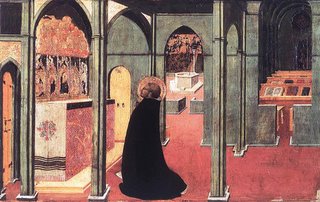

Clearly his greatest love was for God and I have already indicated his love for the Eucharist. However, it is evident too that he had a love for Christ Crucified. There is a story that Thomas prayed before the Crucifix in the posture of uplifted hands, reminiscent of Dominic’s 9 Ways and the Lord asks him: “You have spoken well of me, Thomas, what is your reward?” to which he replied: “Nothing other than Thee, Lord”. This legend indicates two things, which are repeated often. (1) That Thomas frequently prayed before an image of the Lord Crucified (2) And that indeed, he prayed often. In a sermon he said: “Are you seeking an example of humility? Look to the Crucified One.” I have already mentioned St Thomas’ humility but I wish to stress again his prayerfulness, which is understandable when we learn that he saw sacra doctrina as coming from God, the divine Teacher. Indeed, he said he learnt everything in prayer rather than from books. As Tugwell says: “That he habitually resorted to prayer in response to everything that confronted him is also scarcely in doubt. It was well-known that he referred his intellectual difficulties to God in this way. If prayer is the most important activity of the contemplative life, as Thomas says, it is because understanding is always God’s gift.” I can add here just a brief note on Thomas’ theology of God and the role of contemplation. To come to know God, contemplation and prayer is the key, for God is unknowable unless he reveals himself. Thus, in the end, we pass beyond reason, which only enquires, to contemplation that simply beholds Him as He is. For Thomas, contemplation is the greatest joy in this life because it brings us closer to the One whom we love, to Truth and Wisdom.

God reveals himself in contemplation because this is a true sign of friendship, that someone reveals the secret of his heart to his friend. As such, Thomas’ is a affective understanding of contemplation. As such, he also holds that “in things beneath us, knowledge is more important than love but in things above us where our knowledge must remain imperfect, love counts for more than knowledge… it is not the understanding by itself but love that gives us the sight of God.” But this must be balanced by the need for holy preaching and teaching which sanctifies the intellect, not only of the preacher but also of the student. Thus Thomas says: “The ultimate salvation of man is that he may be perfected in his intellectual aspect by the contemplation of the First Truth”, ie God.

Perhaps by way of summary, we can look to Richard Woods OP who says: “God is not so much an object to be thought or even thought about, much less discussed endlessly, as a Presence to be sought. The art of such seeking is contemplative action and its end is mystical union, both in this life and hereafter.”

There is clearly so much more we can learn from this great and holy friar!

May our brother, the saintly Fra' Tommaso d'Aquino, O.P. pray for us.