Courage and Honesty in Ecumenism

In his marvellous little book, 'The Grain of Wheat: Aphorisms', the theologian and cardinal-designate, Hans Urs von Balthasar makes the following observation which is rather honest and even blunt, with regard to ecumenical relations:

In his marvellous little book, 'The Grain of Wheat: Aphorisms', the theologian and cardinal-designate, Hans Urs von Balthasar makes the following observation which is rather honest and even blunt, with regard to ecumenical relations:

"In reciprocal relations between Protestants and Catholics, the most striking thing is that the latter ignore the former completely and no longer give them a thought: they perceive the Protestant principle as a minus of themselves, something they have clearly penetrated once and for all and have found to be too light, something which is not worth the trouble. By contrast, the Catholic is for Protestants an annoyance, a constant object of curiosity: they feel in him the presence of a plus that irritates them, something that they cannot get at and consequently is always challenging them to produce a contradiction."

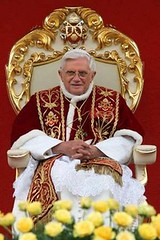

Such an evaluation is perhaps somewhat controversial in our current irenic ecumenical climate but I rather suspect there is a lot of truth in what he observes and if we are honest with ourselves, we will recognize this truth. The question of truth is the core of the search for Christian unity and this quest begins only if we are honest with ourselves and one another. As the then-Cardinal Ratzinger, wrote in 'Principles of Catholic Theology' (1982):

"Two obstacles are opposed to the orientation of Church unity: on the one hand, a confessional chauvinism that orients itself primarily, not according to truth, but according to custom and, in its obsession with what is its own, puts emphasis primarily on what is directed against others. On the other hand, an indifferentism with regard to faith that sees the question of truth as an obstacle, measures unity by expediency and thus turns it into an external pact that bears always within itself the seeds of new divisions."

The present Holy Father's prophetic stance requires both Catholics and non-Catholics to honestly discern if the obstacles he highlights are present in our lives and our attitudes. This honesty is evident in Pope John Paul II's bold initiative in Ut Unum Sint in which he invites "Church leaders and their theologians to engage with [him] in a patient and fraternal dialogue" in order to "find a way of exercising the primacy which, while in no way renouncing what is essential to its mission, is nonetheless open to a new situation", by which he means the

"ecumenical aspirations of the majority of the Christian Communities."

Such open-ness, honesty, genuine fraternal dialogue and attention to truth requires courage. It is as Bossuet says, "Wounds of the heart have this about them: they can be probed to the bottom provided one has the courage to penetrate them." As such, we need courage to ask the difficult questions posed by Ratzinger and even the late Holy Father and it is hoped that our separated brethren will also ask themselves the same searching and difficult questions with equal honesty, frankness and courage. Moreover, Bossuet's aphorism helpfully notes that what we have in our current lack of Christian unity is a genuine wounding of the heart. This is no where more apparent than in the fact that we may not share the Eucharist which is the very heart of the Church, the sign of our unity and bond of love; because our love has been wounded and our unity severed, there can be no Eucharistic hospitality which would not otherwise be a false sign.

But we may still, and indeed ought to, pray together. As we noted yesterday, prayer is the soul of ecumenical renewal and John Paul II encouraged the Church to pray together. As he said in Ut Unum Sint:

"Prayer, the community at prayer, enables us always to discover anew the evangelical truth of the words: 'You have one Father' (Mt 23:9), the Father -- Abba -- invoked by Christ himself, the Only-begotten and Consubstantial Son. And again: 'You have one teacher, and you are all brethren' (Mt 23:8).

'Ecumenical' prayer discloses this fundamental dimension of brotherhood in Christ, who died to gather together the children of God who were scattered, so that in becoming 'sons and daughters in the Son' (cf. Eph 1:5) we might show forth more fully both the mysterious reality of God's fatherhood and the truth about the human nature shared by each and every individual.

'Ecumenical' prayer, as the prayer of brothers and sisters, expresses all this. Precisely because they are separated from one another, they meet in Christ with all the more hope, entrusting to him the future of their unity and their communion. Here too we can appropriately apply the teaching of the Council: 'The Lord Jesus, when he prayed to the Father 'that all may be one . . . as we are one' (Jn 17:21-22), opened up vistas closed to human reason For he implied a certain likeness between the union of the Divine Persons, and the union of God's children in truth and charity'.

The change of heart which is the essential condition for every authentic search for unity flows from prayer and its realization is guided by prayer: 'For it is from newness of attitudes, from self-denial and unstinted love, that yearnings for unity take their rise and grow towards maturity. We should therefore pray to the divine Spirit for the grace to be genuinely self-denying, humble, gentle in the service of others, and to have an attitude of brotherly generosity towards them'."

Hence, it is prayer that will make possible the courage, honesty and open-ness that we have seen is necessary for us to advance in Christian unity and to be prefected in our fraternal love for one another. This Octave of Prayer has been set aside precisely to remind us of what should be a constant hope in our hearts: that one day the Lord will unite us in His Truth and allow us to share the One Bread and the One Chalice of His Body and Blood.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home